I Never Thought I’d Live To Be A Hundred

This week, World On Film visits the African state of Congo. Ah, but which Congo? This was the difficulty I faced when searching for visual material recently. Even the Internet Movie DataBase incorrectly lists many films as being made in ‘Congo’ when they in fact mean the Democratic Republic of Congo. The much larger DRC after all is Africa’s second-largest country and like North Korea, tends to be the greater source of conflict and instability than its near neighbour. But what of the Republic of Congo, the much smaller ex-French colony lying just to the West? It shares a similar history: stripped of its mineral wealth by foreign powers for over a century, racked by waves of civil war and home-grown dictatorships since achieving its independence, and leaving a near-destitute population shell-shocked by the worst depravities of man and facing a bleak future due to lack of infrastructure. For both Congo republics, the story is a shared one, the plights of their people struck by the same destruction.

In the end, however, I did come across one very positive short film showing the efforts made by at least one small organization to give today’s youth in the Republic of the Congo reasons to live for tomorrow.

The Flux Mothers

(2008) Produced by Jacob Foko

“I would like to have a life like every other girl. I want to be intelligent, read, write. I want to have a better life like them. That’s all.”

Holistic approach: In ‘The Flux Mothers’, we see a program designed not only to give Congolese women much-needed job training, but a well-rounded education for a sustainable future.

The DRC is typically referred to as the ‘rape capital of the world’, yet many young women in the Republic of the Congo have also had to face firsthand this most long-term destructive example of social breakdown. Impregnated as young as 12, they now find themselves saddled with children they do not necessarily want nor can afford to provide for. However, rape is not always the catalyst: in an environment without social welfare, affordable education or job prospects, many women will look to men as a means of survival, only to find themselves dumped when impregnated. Destitution and complete lack of self-worth are compounded in rape victims by mental trauma, especially in a strongly patriarchal culture.

“For both Congo republics, the story is a shared one, the plights of their people struck by the same destruction.”

The Flux Mothers introduces us to a Dr. Ann Collet Tafaro, the driving force behind humanitarian aid organization, Urgences d’Afrique, a program designed to train young Congolese woman such as described above in the art of welding, thus giving them a practical skill in high demand across the region. However, practical skills are only part of the equation, since women who register for the program are also given free language and literacy classes, health-care training, and psychological counselling. Tafaro ultimately understands that in Congo’s war-ravaged environment, any attempt at humanitarian aid must go far further than simple job-training. It must also heal the mind and rebuild an individual’s identity from the ground up.

The film also shows that like all humanitarian aid efforts, there are massive holes in the program due to lack of funding – no safety equipment, poor medical facilities, and a paucity of raw materials that any average shop class would stock. Just as the Congolese must make do with the little they have, so Tafaro and her students must do likewise.

Above all, I found The Flux Mothers to be very inspiring, and given that it was made four years prior to this post, it would be interesting to see how much the program has progressed. In the meantime, the film-maker himself has uploaded the film to Vimeo, which means I can present it below. It was produced through an organization called Global Humanitarian Photojournalists, with the aim of attracting donations for Tafaro’s program.

<p><a href=”http://vimeo.com/22004375″>The Flux Mothers</a> from <a href=”http://vimeo.com/jacobfoko”>Jacob Foko</a> on <a href=”http://vimeo.com”>Vimeo</a>.</p>f*****

The Opaqueness of Sustainability

Sometimes, getting visual material to watch for a particular country can turn up some truly bizarre results.

Several years ago, I came to hear a few tracks off a new album I mistakenly believed to be the work of the late Donna Summer. It was an obvious mistake: after all, the album was credited to a ‘Donna Summer’ and given the title ‘This Needs To Be Your Style’, which seemed to fit – was not Donna Summer a woman of great style? Then there was the ‘music’ on the album itself, a motley assemblage of aural cacophony that even Bjork would only think fit to record after six months of heavy acid usage, occasionally interspersed with twisted samples of familiar tracks by the disco queen herself.

What I did not know was that ‘This Needs To Be Your Style’ was in fact the work of ‘Donna Summer’, aka British electronic and breakcore obsessive, Jason Forrester, who adopted Summer’s name for stage purposes. I mean, it’s obviously really, isn’t it? It didn’t help. Knowing the real intent of the album did not somehow magically reassemble the mad mix into something coherent – which for all I know is what breakcore exists in the first place.

Many years later and not long after the real Donna Summer released what would be her latest – and last – album, I found myself given the dubious pleasure of editing bid proposals by various organizations hoping to secure international conferences. It could be an interesting job in theory, but for the fact that I quickly discovered that none of the bidding hopefuls knew the first thing about how to sell their host city as the site of a potential global congress. Thus would the Power Point presentations and PDFs be a soul-destroying kitchen-sink collection of random facts interesting to no-one and of dubious connection to the main thrust of the proposal’s argument, which itself was only optionally present. Perhaps the authors felt that to assault their audience with a barrage of facts and figures would beat them into stupefied submission, if not baffled silence, causing them to cave in completely.

“Sometimes, getting visual material to watch for a particular country can turn up some truly bizarre results.”

So, then, we see that context is everything, but your ignorance of that context does not always mean your hosts know what they’re talking about. Which brings me to this Congo-focussed oddity.

SOPI Architects, an architecture/urban planning firm based in the UK and Cote D’Ivoire, once put together a proposal for achieving sustainable development in Brazzaville and beyond. Following what has to be the longest company ident in history, we see a curious mish-mash of a film that centers around showing us a long text-based feasibility study that seems ultimately to conclude that what the Republic of the Congo needs more than anything are more attractive buildings. Well, you would expect an architecture firm to say that. The problem, however, is that the other 98% of the video (8% of which worships the ident) does not really build up an argument in this direction, preferring instead to take the scattershot approach of throwing in facts and figures about the country’s development problems across the board.

At least I assume that’s the case, given that the text is too small to read, and not on screen long enough to read in any case. It appears for all the world as if someone has filmed the pages of a book, more to show you what each page looks like rather than an effort to help you read it. There is also the apparent assertion that you are fluent in both English and French, given the randomly-inserted talking head video clips predominantly in French despite the English text, and not subtitled. The footage is also a strange collection, at one point a long self-congratulatory sermon from no less than the nation’s president, Denis Sassou Ngouesso on forest preservation to clips of flood victims complaining – and quite rightly – about the ease with which their villages are frequently underwater.

Like ‘This Needs To Be Your Style’, it’s all over the place. One could argue that I may have failed to grasp the finer subtleties of the argument – maintaining forests + shoring up river banks = build more duplex apartments – but I remain skeptical on this point. At any rate, if you would like to make sense of the presentation, you can watch it below.

*****

Next Time

“The island’s seemingly impenetrable mass of opaque green palm trees and tooth-jagged mountain ranges easily suggest the untamed exotic Javan wilderness far from Batavia’s comparative civility of more than half a century ago”

World On Film visits the Cook Islands in the South Pacific, looking at examples of their use in storytelling – typically as a stand-in location for somewhere else. You can see a trailer for one of these examples below. We also take a good look at the archipelago as it truly is, and I can already say it’s convinced me to go there someday. That’s next time.

The Other Side Of Life

A bit of a gear-change this time around, as cinema is not really high on the agenda for the country featured. Nonetheless, there is plenty to watch – and a lot to think about.

Unless you’re deaf or know someone who is, it’s reasonable not to give much thought toward those who are – what options they have in life, the extra lengths they have to go to in order to compensate, and how they are treated by others. Still, we might think, society does offer support: the deaf are taught sign language and how to lip-read, the partially-deaf qualify for hearing aids, and it’s not as if being deaf prevents you from finding work. And quite rightly.

Still, imagine a place where the deaf are ignored simply because they can’t hear; where they are given no education and no job prospects, left to do absolutely nothing from the day they are born until death comes to claim them.

Unfortunately, there are places in the world where some don’t have to imagine this scenario.

Deaf In The Central African Republic

That video was put together by the Central African Republic Humanitarian and Development Partnership Team, a non-profit organization working to coordinate the various entities trying to improve life in the country. Help was supplied by the Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf.

Now it would be easy to be highly critical of this lesser-known African state for what the video shows – that CAR society cares little for the weak and infirm. However, context is everything and we need to zoom out a little.

“Imagine a place where the deaf are ignored simply because they can’t hear”

The Central African Republic is one of the poorest nations on the planet, with the International Monetary Fund placing it 178th out of 183 in 2011 in terms of GDP. Part of a former French colony, the CAR has a population of approximately 4.5 million who have suffered at the hands of foreign and domestic oppressors for as long as they can remember. A hundred years ago, they were slave labourers to their French overlords and, following the country’s independence in 1960, abused repeatedly by home-grown dictators fighting each other for control of their fate (- one even declaring himself their emperor). Military rule is still quite recent, with fair elections taking place for the first time only in 2005, yet this is seen as a hollow victory.

Although the land is rich in natural resources and suitable for agriculture, a near-total lack of infrastructure and a complete absence of government subsidies has meant there is no way to make a living from either. In other words, it isn’t just schoolteachers going unpaid. And, inevitably, the rampant poverty has led to social instability, extortion, and violence exacerbating the problem still further, with a government powerless to stop those seeking to profit by it.

Under The Gun

Produced by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs.

Consequently, the Central African Republic is entirely dependent upon humanitarian aid for its survival, hence the need for the HDPT and their efforts to coordinate that aid. This is particularly the case in the north, where the terrorism is strongest. Even there, however, aid groups try to provide children with education. In the previous video, teachers expressed their frustrations at the temporary nature of any schools established, particularly in the bush. UNICEF, on the other hand, is more upbeat.

Produced by the HPDT and UNICEF.

Starting Point

The focus in this entry has been primarily on education, but for more videos on a range of issues relating to development in the Central African Republic, please visit HPDT’s official youtube page. For more on what HPDT does and background information on the CAR, their homepage (see above) is a good place to start.

“A hundred years ago, they were slave labourers to their French overlords and, following the country’s independence in 1960, abused repeatedly by home-grown dictators fighting each other for control of their fate”

If you’re reading this blog, you’ve likely enjoyed a comprehensive education, and yet if you’re like me, you probably have many complaints about its rote-based, corporate-driven nature. Sometimes it’s good to remember that it could be a whole lot worse.

Related Viewing – CAR and African Cinema

The Silence of the Forest

Amazingly, the CAR does have the beginnings of a film industry, with Le silence de la forêt the first full-length feature produced in 2003. Shot on location, the multinational film tells the story of an well-educated CAR native deciding to throw in his job and free the local pigmy tribe of their oppression by the ‘tall people’. However, they are inflexible to change and unable to see the benefits his urbanised knowledge and expertise will bring them. Based on the novel by Marcel Beaulieu, The Silence of the Forest can currently only be seen at film festivals and has received mostly positive reviews – including that from California Newsreel.

White Material

World On Film has explored the poverty-fuelled social upheaval of a former French African colony before, in Claire Denis’s discomfiting drama, White Material. “While White Material’s plot is entirely fictional, it recreates a world the younger Denis knew all too well: civil unrest, poverty-fuelled extremism, and anger at the nation’s French overlords. The scenario applies to any annexed African state, and Denis deliberately paints her narrative in broad brush strokes, with locations remaining unnamed and specific real-world examples of conflict vague. Click here to read the full review.

The Burundi Film Center

The CAR isn’t the only central African state with a budding film industry and more importantly, a similarly troubled history. Last year, World On Film discovered how one NGO is helping to empower the people of Burundi to tell their stories. “In 2007, a group of international film-makers set up the Burundi Film Center, a non-profit initiative designed to provide interested young Burundians with an opportunity to realise their cinematic dreams. The nation, emerging from the throes of civil war, cross-border conflict and poverty, was seen as having reached a turning point where the population could at last begin to express their cultures, celebrate their differences and realise their creativity.” Click here to read the full story.

Next Time

A country torn apart by war. Living just outside the danger zone, one man is determined not to let the real-world interfere with his own private paradise, until he loses his job and his self-worth. Only then does the war come close to home – but has he caused the conflict himself? Humanity and hubris in the thought-provoking Chadian film, A Screaming Man, next time on World On Film. You can see a trailer below.

All That Is Real Is You

In this edition of World On Film, we follow a young man caught between two worlds and who goes in search of his roots all the way to Cape Verde, where he happily discovers that he has –

Cabo Verde Inside

(2009) Written & Produced by Alexander Schnoor

“What does it mean to be Cape Verdean? Being a good dancer? To not stress one’s self out?”

Half-German, half-Cape Verdean Alexander Schnoor gets in touch with his ancestral roots in ‘Cabo Verde Inside’.

I’ve long believed that people don’t give nearly enough thought to the way in which their inner yearning for identity shapes their every interaction with the world around them. In a sense, the narcissist is the most honest of human beings – they consciously assert that everything within their world is ultimately about themselves and proceed through life with that premise as the lens through which everything is viewed. The narcissist only becomes a figure of dislike when they interact with someone who doesn’t share their parochial assertions – someone who is consequently offended because the former does not validate their own sense of self-worth, like a rhinoceros unconcerned by the existence of an ant.

Yet we are all narcissists at heart by design: we anthropomorphise the world around us and find nothing more fascinating than the actions of our own species and how we feel in relation to those actions. Reality is entirely shaped by how we focus upon those elements of the world that validate who we are, and consequently blind us to everything else beyond. Only through social evolution have most of us learned to internalise our selfishness through recognition that our survival works better as a group, which means acknowledging the needs of others. Read political scientist Francis Fukuyama’s most well-known book, ‘The End of History and the Last Man’, and see the way in which his proposition that democracy is the final evolution of society must first be understood in terms of thymos, the Greek word loosely translated as ‘self-identity’. Even beneath the sexual drive, argues Fukuyama, is the base need of the individual to have their sense of being recognised and agreed upon by everyone they meet. We befriend those who do and find reasons to dislike those who do not for reasons that are not necessarily connected with our underlying discomfort with them.

The quest for the self, however, is not undertaken on a level playing field. With much of it defined by race and nationality, there will always be a disconnect and a good degree of soul-searching among those who do not fall into such simple categories. Hence the common practice by people whose identities are more complex because they may be migrants, or the children of migrants, raised in one society, but strongly informed by the ethnicity and culture of another – a society of which they may have no direct experience. At a certain point of their development comes the yearning to visit the land of their ancestors, typically justified as a spiritual journey. More telling however is when their reason is given as a need to “find themselves” and we see the true root cause.

“The quest for the self is not undertaken on a level playing field. With much of it defined by race and nationality, there will always be a disconnect and a good degree of soul-searching among those who do not fall into such simple categories.”

The journey of self-discovery includes meeting fellow migrant offspring, who champion pluralism and adaptability as the Cape Verdean’s greatest strengths.

The time spent in the ancestral homeland is frequently an ambivalent success: on the one hand, the individual feels the joy of finally being able to connect with the other half of themselves, nothing less than the validation of an identity not understood by the locals back home. Though largely experiential, the adventure seems to nevertheless answer questions never consciously made yet obvious – all pointing back to the two fundamental questions we all have of existence – Who am I? and What do I want? Yet it is also a honeymoon period: stay too long and the reality of the homeland punctures the elation, creating an internal conflict. From here, the person may be unable to reconcile their ancestry with the values instilled by those with which they were raised or find them more compatible with those back home. Here then, is the point when they really have to decide who they are.

Alexander Schnoor, half-German, half Cape Verdean, decided to identify his own inner yearnings back in 2009 when, armed with a video camera and a creditable skill for film-making, he set off for his ancestral homeland for the very first time hoping to answer the question, What does it mean to be Cape Verdean?

To the viewer’s benefit, Schnoor is just as committed to creating a narrative build-up to his quest as he is in finding himself. Cabo Verde Inside begins in Schnoor’s hometown of Hamburg, Germany, and spends time both framing the voyage to come and the process by which it took place. Schnoor doesn’t simply hop on a plane to Boa Vista, but first explores the Cape Verdean influence closer to home. Economic hardships on the islands back in the 1970s resulted in a mass exodus from the islands, with the result today that more Cape Verdeans live abroad than do within its 10 islands. Thus Schnoor searches for answers first in the local expat community before moving on to Maastricht where he meets a Creole woman of similar ancestry. The latter goes on to suggest that diaspora and racial mixing are the underlying reasons for the Cape Verdean easygoing amiability. The sentiment is oft-repeated by others throughout the film and unsurprisingly, is much to Schnoor’s liking.

It is through this perception filter that Cape Verde is presented. From the quiet, agrarian-based communities of Sao Vicente and Sao Nicolau to the comparatively bustling main settlement of Santiago, the island nation is the very model of a developing world Eden. Locals almost uniformly speak of their social stability while reaffirming its mixed racial demographic and tolerance as the root cause, with one interviewee even suggesting that Cape Verdeans are the model for the future of humanity.

“To the viewer’s benefit, Schnoor is just as committed to creating a narrative build-up to his quest as he is in finding himself.”

Upon arrival, Schnoor finds exactly the kind of people he hoped to find, validating his voyage of self-discovery.

And the islands themselves are fascinating and beautiful. Geographically, Cape Verde is a kind of North Atlantic Hawaii, formed by the same shifting hotspot volcanic activity. The mountains are jagged and dramatic, the beaches long stretches of shimmering sand, and the waters a rich azure blue. Couple this with the island chain’s isolated character and you have the textbook resort getaway for the rich and the appearance at least of a Brigadoon-like simplicity. In addition, Schnoor clearly has an eye for visuals and better still, a good understanding of editing, and thus turns out a appealing video postcard of his trip that never feels overlong.

The problem with the film for me then is that Schnoor, who spends only two weeks in Cape Verde, is very much in the ‘honeymoon’ phase of discovery. He is brought into the island community via his own relatives who are happy to meet him, neighbouring farmers welcome him and everywhere the joie de vivre directed his way is what you would expect of someone who went up to the locals and said “Tell me why you think Cape Verdeans are so awesome!”

Cabo Verde Inside is, in short, a paean to a people living in Shangri-La because the film-maker is at a point in his own personal development where he needs them to be doing so. We are viewing not so much what is actually there, but the happiness of Schnoor’s psyche made manifest in rose-tinted brilliance as long-held desires within him finally connect with the one-and-only people who can mirror their need.

The real Cape Verde, long a Portuguese colony with a turbulent history, is never explored. Even the economic hardships mentioned above go without mention – the locals just seem to have left because they’re open, highly-adaptable people who can live anywhere. The roughly 20% who live below the poverty line are presumably content to make do on land with few natural resources.

A former Portuguese colony, Cape Verde is strongly dependent upon agriculture, fishing, and tourism. The underlying mechanisms of the country are not, however, especially germane to the film’s raison d’etre.

It isn’t that I don’t believe Cape Verdeans are warm, welcoming and happy. They have a reputation for being just that. Even the Wikipedia entry makes this point. They live in a warm climate, the population is low thanks to the mass exodus so everyone has the space to be comfortable, and life is uncomplicated. I just didn’t learn a great deal about them in this film. The population is low because people within living memory were starving following the collapse of the slave trade and the withdrawal of the Portuguese colonial masters. People have the space to be comfortable because most of them left. Life is uncomplicated because Cape Verde has been neglected for the last 40 years and again because most of the population left. What does it mean to be Cape Verdean? Living almost anywhere else.

“Cabo Verde Inside is, in short, a paean to a people living in Shangri-La because the film-maker is at a point in his own personal development where he needs them to be doing so.”

All of which is ultimately demanding too much from Schnoor, when by now, we understand precisely where he was in his life while making the film and why it couldn’t be anything less than Disneyfied. Meet anyone of mixed origins who has grown up in one place and later visited their ethnic birthplace and ask them how things were those first two weeks. Very likely this will be their experience. Had Schnoor left Germany behind and actually relocated to his ancestral homeland, what might he have to say of it today? The title itself is explicit enough – it is not ‘Inside Cabo Verde’, but Schnoor finding Cabo Verde Inside. I’m glad he had such a positive experience, but I’ll have to look elsewhere to discover Cabo Verde For Real.

But enough from me. You can watch the whole thing free and legally for yourself right here:

*****

Next Time

“The Cayman Islands are famed not only for being a popular tropical getaway, but as an especially popular tax haven for off-shore banking. Nonetheless, the damage to Paradise has been done, the Western world have destroyed the local society by raising it to a level of modernity that benefits only those who colonized it and who now leave the resulting cultural mish-mash to its own, poorer ends. Or, at least, this is how writer/director Frank E. Flowers sees the Cayman plight.”

Paradise lost in the 2004 melodrama Haven, up next on World On Film. To see a trailer, click below.

Consequences

A couple of documentaries go under the spotlight on this week’s trip to Side-step City. Up first:

The Town That Was

(2007) Directed by Chris Perkel & Georgia Roland

Once a major hub in the Pennsylvania anthracite coal industry, little remains of the town of Centralia. Long-since demolished houses leave behind little sign of habitation, while below, a fire rages on.

Recently, I had the chance to see this evocatively-titled documentary that had sat on my Must Watch list for several years, concerning the fate of a most unconventional ghost town. Part-inspiration for the game/Hollywood flick Silent Hill, Centralia, Pennsylvania, was once a thriving community until deadly subterranean fires forced all but a handful of stubborn long-term residents to evacuate. Established in the early 1840s, it was a key player in the region’s massive coal mining industry and its core reason for being until alternative forms of energy took hold and the practice became unprofitable in the 1960s. Early the same decade, the local council hired a team to clear away the local landfill. Somehow, no-one stopped to think that the usual practice of burn-off might not be such a good idea given the locale and in 1962, the fire found the coal seam of the disused mine and has been burning ever since. Indeed, it’s believed that it will be some centuries before it finally dissipates.

Centralia was a proud and tight-knit community, but when the citizens began to succumb to the toxic gases erupting from every fissure in the ground and children began to fall down sinkholes, relocation became highly-desirable. The local government assisted by buying back houses, officially declaring Centralia ‘eminent domain’, which meant that anyone still remaining no longer owned their property and reduced to the level of squatters.

“Somehow, no-one stopped to think that the usual practice of burn-off might not be such a good idea.”

Proud Centralian and long-time holdout, John Lokitis Jr. stands in front of the smoky wasteland. Much of the documentary focuses upon his lone efforts to keep the town's bare skeleton going.

By the time of The Town That Was in 2007 only 11 residents remained, and they attempted unsuccessfully to sue the government over the eminent domain claim. Through a series of interviews, location and archive footage, the documentary shows how the once thriving town came to be in such a sorry state. With wisps of smoke wafting around its near-empty streets and driveways leading to empty housing estates, Centralia is every bit the modern-day ghost town. Principal interviewee Jon Lokitis Jr. is the most colourful character. When not at work in a job some two hours drive away, Lokitis stubbornly refuses to let the town release its last gasp. When he’s not moving council grass and repainting peeling park benches, he’s erecting fairy lights on the telephone poles in time for Christmas. It’s a dedication taken to extremes that can only cause his ‘traitorous’ ex-neighbours, now comfortably residing in nearby boroughs, to speculate on his mental wellbeing – his claims that the poisonous inferno literally eating the ground beneath his fate is in no way dangerous earning particular disbelief. The prevalence of this uncompromising resident does make the film rather one-sided, although from an entertainment perspective, it’s not hard to understand why. Even the current IMDB synopsis for this entry describes it first and foremost as “a portrait of Jon Lokitis Jr.”

Things have moved on a bit since 2007, and not for the better. However, since I can happily tell you that the film is freely (and legally) available to view online, I’ll let you discover the final chapter via Google for yourselves. For now, sit back and enjoy the sad tale of The Town That Was. View the official trailer below for a taster, then go here and watch the whole thing. Note: in order to bring it to you for free, the site has placed sponsored advertising at the beginning and mid-point of the film, and spooling through will result in it restarting from the beginning, so be prepared to sit through the film in one setting – definitely worth it, I think.

Google Earth enthusiasts might also be interested to know that Centralia’s main roads are available on Street View, allowing you to see what’s left. Get in now before they update their source photos – there may be nothing left next time!

On a side note, I was amused to discover there are no less than 12 places in the U.S. called ‘Centralia’. Sure, it’s a bit classier than ‘Gobbler’s Knob’, or the equally imagery-inducing ‘Whiskey Dick Hill’, but it’s not that special.

*****

College Conspiracy

(2011) National Inflation Association

College textbooks are given minor updates every year, forcing every new batch of students to purchase the latest copy - according to the NIA, just one of the many scams colleges maintain in order to induce profit.

College – the biggest scam in U.S history. So say the National Inflation Association, a non-profit organisation dedicated, according to their official site, “to preparing Americans for hyperinflation and helping Americans not only survive, but prosper in the upcoming hyperinflationary crisis”. Society is paying for an unnecessary overemphasis on college education – and in turn, an overemphasis on specific fields of study, such as law – and the bubble is about to burst. Aspirations of wealth and success have become synonymous with a tertiary education, but the playing field remains level when everyone has a degree.

Except that now, they also have a massive college debt for qualifications that thanks to seriously increased competition, did not yield the career of choice and condemns them to spend the rest of their lives paying for it. Once the province of the banks, college loans are now provided by state funds – funds that a soaring educated class of underemployed wage earners cannot hope to repay. Who then but the tax payers to foot the bill and a state forced to print more currency leading to a vicious cycle of hyperinflation? Meanwhile, a rising population demands ever more from agriculture, yet no-one is interested any longer in making a career in it, thanks to dreams of an urban high life as a high-paid doctor or lawyer.

“Society is paying for an unnecessary overemphasis on college education – and in turn, an overemphasis on specific fields of study, such as law – and the bubble is about to burst.”

'College Conspiracy' argues that an overemphasis on university education has flooded the job market, effectively rendering college degrees worthless.

Such is the premise of College Conspiracy, an urgent call to all Americans to wake themselves up from the myth of college education and the inevitability of debt slavery, and to the alternative paths to success, a vast arena of industry necessary to the continued survival of our world, from farming to all forms of local business.

Whichever side of the debate one may find themselves on, the documentary cannot fail to provoke a response. Though U.S-centric, College Conspiracy’s arguments apply just as easily to tertiary education in most of the world, whether it’s simply the high price of a university degree to its ever-diminishing value as means of gaining a leg-up on the career ladder. It has become an unchallenged mandatory path to success and, rather like the Confucian exams of old East Asia, the divider for class, opportunity, and respect, an attitude which continues to define that region of the world.

This however is a telling point: for many, a college education is essential, not simply for those who have a clear career path in mind, but even for those simply seeking a standard office job. It is precisely because society regards it as mandatory that simply having a degree is required even to open the most average of doors. It therefore would have been nice for College Conpiracy to have devoted more time to illustrating further the alternative paths to not only wealth and success but general and basic financial security beyond university. Also, the diminishing agriculture sector, while massively important, should not be the only example – the message shouldn’t be interpreted simply as “Lawyers suck! Your tractor needs you!”

Self-made professionals can occupy a whole raft of industries, which is the intended conclusion, just not adequately explored. Whatever the field (excuse the pun), the NIA’s underlying point for students is that as their country slides ever further into recession, the last thing the world needs are more solicitors searching for loopholes in property laws and instead a new generation of citizens armed with skills from which we can all benefit, and that for those who develop their talents with such skills, the rewards are there. Until all sectors of society, especially employers accept this however, it’s a bit much to simply expect youths looking to secure a future to turn their backs on university. Many are well-aware of the farce tertiary education has become and the debts they will accumulate, but don’t feel they have much choice in the matter. The underlying message of the film is not invalidated, but it will take more than simple awareness of the problem to rectify it, and a commitment on the part of those with the power to effect change. Nonetheless, awareness is the first step and interested parties can watch College Conspiracy for free via here, courtesy of NIA’s official youtube page:

*****

Medley

Last week, World On Film travelled to Barbados, a former British colony, where the cultural traditions, especially the music, had left a long lingering influence. This week, we spend time in the only Central American nation once under British hegemony, once known as ‘British Honduras’. Music is also the theme of the main feature, though this time the natives aren’t kitted out in full naval regalia for a knees up in time to the strains of a brass band. However, like the Land Ship Association, their Belizean counterparts are practitioners of a dying musical tradition, one rapidly being consigned to the dustbin of history unable to compete with the appeal of the Lady Gagas of the world. But first, a short trip into the inner workings of Belize’s annual canoe race, explored in the film:

La Ruta Maya: A Victory From The Sidelines

(2009) Directed by Laura Murphy

La Ruta Maya is a major annual Belizean canoeing competition spanning 4 days and running along the Belize River from San Ignacio to Belize City. It galvanizes not only the locals, but attracts many spectators and participants from across the Americas. Through Laura Murphy’s brief documentary, we learn both the scope of the race and the many challenges and pitfalls involved in getting it off the ground, with particular focus on the contributions of the many support teams present, ie – the ‘sidelines’ of the title. The story is told from the point of view of some of these key participants, who all clearly have a passion for the competition. There is only so much you can do in 8 1/2 minutes, although I think it would have been more interesting to have applied a far broader focus of all things La Ruta Maya. For example, this means we don’t really hear from the rowers themselves, or indeed the many dedicated Belizeans who flock to the shores of the river every year, which would go a long way toward really transmitting the excitement of the event, partly neutered by 5 minutes spent describing how problematic it can be.

“It would have been more interesting to have applied a far broader focus of all things La Ruta Maya.”

Nor do we really learn much of the background to La Ruta Maya, why it came about in the first place (aside from a half-remembered anecdote about a group of canoe-loving friends that isn’t adequately explored), its cultural raison d’etre or even why it is held on Baron Bliss Day (a fact I only discovered afterward via Google). The very title of the piece makes it clear that emphasis is deliberately placed upon those necessary incumbents behind the scenes, but such an approach limits the appeal of the overall effort with a general audience. It’s 8 1/2 minutes that could have formed part of the much larger tale of conquering 64 miles of river without respite. Still, for all I know, it was only intended as a vignette for those in the know rather than having such wide viewer appeal, and certainly, I have learned something of this major sporting event in the process.

*****

.

Three Kings Of Belize

(2007) Directed by Katia Paradis

You can visit the film’s official Facebook page by clicking here.

Three Kings Of Belize brings the viewer into the everyday lives of three Belizean musicians – each very different in character and outlook on life, but united by their passion for music. Now in their autumn years, Florencio Mess, Paul Nabor and Wilfred Peters have lived long, uncomplicated lives. Today, their old hands are not as confident as they once were, but all three have the same zeal for their craft despite many hardships and the passing of fame. Touching, warm and honest, the film is the triumph of a confident director sure of her material and the compelling characters she brings before the camera.

Indeed, one of the hallmarks of a good director is the ability to let the story tell itself without long periods spent in post-production attempting to spice up the end result with jump cuts and special effects for a cynical audience. Instead of this, Katia Paradis simply shows her subjects and their environment at a pace matching the sleepy perambulation of their lives. It is very likely also a function of budget, but in no way should that be a criticism, for Three Kings is a triumph of the ‘less is more’ approach, and all the more mature for it. Whether it’s the solitary quietude of Mess’ and Nabor’s rural lives or the comparatively active, urban adventures of Peters, there is always a sense that we are seeing the truth – almost as if we were there filming the subjects ourselves. It is a documentary without narrator, and so in between dialogue scenes, the camera simply points at the world each of the men live in, often saying far more than any verbal storytelling would. In this way, three corners of Belize come to life in vivid shades of colour without overt comment, although the love each musician has for his country comes through in their desire to uphold cultural traditions – Peters even going so far as to wonder why anyone would want to live anywhere other than the country of their birth. It is a simple nationalism, for once devoid of destructive political design.

“Three Kings is a triumph of the ‘less is more’ approach, and all the more mature for it.”

Sidelined by a culture now more interested in pop music, solitude and regret now fill the long spaces between the notes for these guardians of Belizean folk tradition.

The abundance of these quiet intersections in a 90-minute film does however make it at times a little too sleepy, though in the process giving the viewer a very telling snapshot of each man’s world: gone are the days when live performances of their traditional musical styles were popular with the masses, not to mention the declining popularity of the genres themselves – as Nabor and Peters themselves lament – and thus regular employment has long since dwindled, leaving them to be self-sufficient. Yet even here, they retain their dignity, with Mess for example a successful crop farmer and craftsman. While wistful nostalgia gives them pause on what they might have been, all three are realists.

As the very human exploration continues, one cannot help but feel sorry for these men. Each is clearly aware that he belongs to a different age, and unlike the days of their youth when they themselves took the cultural baton for another generation, the modern world simply isn’t interested. While all three bear this knowledge with fortitude, it is clear how saddened they are by it. After all, what is a performer without a captive audience? Yet sequences with fans both home and abroad clearly show they are still able to bring joy to others the only way they know how. Paradis has effectively documented the passing of an era – the compact disc has triumphed and pop music renders folk song alien to the common ear.

The ‘Three Kings’ however will live on, in this rewarding and honest journey through their lives. Aside from its occasional slowness, it has warmth and humanity at its heart brought to life with realism and dignity. It’s a strong feature debut from a promising director and I will be interested to see where she takes us next.

*****

Up Next

The Christmas season is upon (some of) us, though not to worry – this won’t be an excuse to review some nauseating yuletide film. My idea of viewing pleasure during the festive season is to watch ghost stories, preferably those of antiquity. Therefore, World On Film will be taking a sidestep for the final posting of 2010 by looking at Jonathan Miller’s excellent adaptation of the M.R. James classic, Oh Whistle And I’ll Come To You, My Lad. No trailer exists that I know of, but here’s the first minute, which basically introduces the whole premise:

You can also find the original short story, now out of copyright, by clicking here.

The Coming Of The Church Mountain

World On Film is currently on a break from its prime directive: to seek out episodes of cinema from across the globe and hopefully represent every country (a proposition you will quickly have recognised as being utterly mad). The definition of this raison d’etre is being stretched to breaking point during the respite so as to provide an excuse for other topics of personal interest, though certainly film is still the tie that binds them. This time around, we look at an example of film bringing an episode of history to life and the way it therefore provides a real immediacy to the event, even decades after the fact.

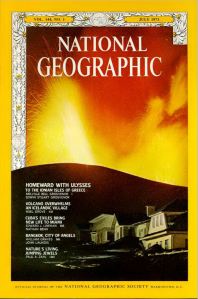

The island of Heimaey prior to 1973. The ancient volcanic cone of Helgafell stands to the right, a testament to the subterranean forces soon to be re-enacted.

Somewhere in the middle of the 1980s while I was in short pants and discovering the concept of libraries, I discovered the far-away and seemingly-unpronounceable island of Vestmannaeyjar (vest-man-ay-yar). The colourful children’s hardback, helpfully titled Volcanoes would, I hoped, promise just as much wonder and excitement about these powerful, world-shaping mountains of fire as had Felicia Law’s definitive work on the subject, also efficiently titled Volcanoes. In its namesake, a group of schoolchildren living on Vestmannaeyjar’s chief island of Heimaey were poised in the cold outdoor air to learn the complex, yet abundantly demonstrative science of volcanology. Such a school outing would be considered highly dubious at best in my home town, where the only time the ground exploded was when the local council blew up sections of a nearby hill in their quest for granite. The Icelanders however had two volcanoes on their doorstep, and one had literally exploded into existence only a few years earlier.

“The Icelanders [of Vestmannaeyjar] had two volcanoes on their doorstep, and one had literally exploded into existence only a few years earlier.”

The Fires Of Muspelheim

“We felt its hail of cinders long before we saw the volcano’s fire, glowing like a midnight sunrise through the mizzling rain.” – Noel Grove, An Island Fights For Its Life, National Geographic, July 1973.

It was a cold and unexpected awakening that greeted the town of Vestmannaeyjar and its 5,000 inhabitants on the 23rd of January. At approximately 1.55 AM, the ground along the east coast literally tore itself apart barely a kilometre from the slumbering community and stretching 3 kilometres all the way down to the southern tip. Heralded by an ominous rumbling, a curtain of lava rose 150 metres into the night sky the entire length of the fissure, as though transforming Heimaey into a giant Hadean theatre awaiting the start of some hellish performance. Yet the drama was very much underway and soon, the outpouring of molten rock would confine itself to the north-east of the island, where it enveloped the farmland housing the local church. After less than a month of constant activity, the eruptions had formed a mountain 200 metres high – one that would continue to grow for the next 4 months.

Fortunately, Heimaey had seen tempestuous weather conditions in the days leading up to the eruption and all of the town’s fishing boats were moored in the harbor, ready for use. The population was therefore able to be swiftly relocated to the Icelandic mainland – primarily Reykjavik – where they would stay for the next several months as the volcano unleashed its fury upon their home. Some 200 locals would stay on to fight the sea of ash threatening to crush every household by its sheer weight, and, in the months to come, literally stop the flow of lava from destroying the harbour. With their whole industry based on fishing (in turn accounting for approximately 10% of the national total), the idea of letting nature take its course was never seriously debated. However, their battle would not be won easily.

“Heralded by an ominous rumbling, a curtain of lava rose 150 metres into the night sky the entire length of the fissure, as though transforming Heimaey into a giant Hadean theatre awaiting the start of some hellish performance.”

Ash-covered houses with views of nearby Bjarnarey Island (above) lose their eye on the neighbours to an encroaching lava field (below) mere months later.

As the eruption continued, the geography of the island would be substantially altered, firstly by having its total size increased by 2.24 km², but more crucially, by nearly closing off the all-important harbour entrance. This, more than anything else, would signal the death of the settlement if it were not stopped, and with every passing day, the ever-expanding lava field to the north threatened to close the gap between the mainland and the long peninsula to the north that sheltered the port from extremes of weather. The danger to the town also increased dramatically a month into the eruption when the entire north flank of the volcano collapsed under its own weight. A seemingly never-ending ocean of lava now poured unchecked by even the mountain itself toward the town, accelerating the growth of the lava field, intent on closing the harbour forever.

With both the crucial waterway and the settlement itself directly under threat, contingency plans were needed fast. Early ideas included cutting through the lowest point of the peninsula, effectively creating a new harbour, and bombing the crater. The former would be dismissed as too cumbersome while the later was determined to be likely as dangerous to the town as the river of fire itself. It would eventually be agronomist and fellow rescue worker Páll Zóphóníasson who proposed stopping the lava flow with seawater. With the help of pumping equipment already installed in the larger sea vessels, the islanders quickly began aiming their hoses at the encroaching mass. The process of nature was duly halted, with the gap no more than 100 meters and a massive lava flow having crushed half the town as well as destroying several fishing factories. Under the impact of the sprayed seawater, the edges of the lava flows became towering walls of solid rock, while the still-flowing rivers of fire behind were diverted away from the town.

“A seemingly never-ending ocean of lava now poured unchecked by even the mountain itself toward the town, accelerating the growth of the lava field, intent on closing the harbour forever.”

Their livelihoods saved, the inhabitants of Heimaey were significantly less concerned about the massive devastation that lay in wait for them upon their return to the island. That same destructive coating of ash could after all be harvested to dramatically improve the local runway as well as provide solid foundations for new housing. The tempered volcano meanwhile would provide free geothermal energy for most of the decade – though initially, the sulphurous gases slowly escaping from the drying rock would render the atmosphere toxic, with one fireman rescuer asphyxiating in a cellar and becoming the eruption’s only victim.

By early July, the mountain, initially dubbed ‘Kirkjufell’ for standing where the church had months earlier, now officially known as ‘Eldfell’ (Fire Mountain), had ceased eruptions and towered some 220 metres above the landscape, its neighbour: the ancient cone of Helgafell, which had dominated the island’s fate when it exploded into being some 5,000 years earlier. 12 kilometres to the south-west, the island of Surtsey stood quietly in the half-mist – only 10 years earlier having risen angrily out of the water to frustrate the cartographers by becoming the nation’s southernmost point of land. Over the next year, the townspeople returned, and set about the task of clearing away the ash from the home they would rebuild.

“Over the next year, the townspeople returned, and set about the task of clearing away the ash from the home they would rebuild.”

On Film

Several short films captured the latest chapter in the Vestmannaeyjar saga back in the 1970s. The Heimaey Eruption, from which the images you see here are taken, is one such example. Written and produced in 1974 by Alan V. Morgan, it gives a good account of the unfolding drama, thanks to some excellent footage. Viewers are given a brief overview of Iceland’s volcanism and the forces that are literally pulling it apart, before the action travels to Heimaey, where Eldfell is slowly flattening the town. Two other films if you can find them are Day Of Destruction, produced by Kvikmyndagerðin Hljóð og mynd, and Fire On Heimaey, produced by VÓK-Film hf (both in colour and having English narration).

Someone has posted The Heimaey Eruption to youtube, so never mind my rambling waffle – take a look for yourself:

Further Viewing

Gerhard Skrobek and Hermann Luschner produced some spectacular film of the eruption and its impact on both the town and the rescue workers. Having now made its way on to (where else?) youtube, you can view it here:

And here:

Thanks to the work of Morgan, Skrobek, Luschner and others, we have the story of Eldfell immortalized in sound and motion, providing that immediacy so important 37 years later when it all seems so distant and unreal: perhaps not to the people of Iceland, used to one of the most dynamic and rapidly-changing landscapes on Earth. How amazing it would have been to have actually seen footage of the Tambora eruption of 1816 or indeed Krakatoa in 1883 – two eruptions that changed the world forever. How incredible then to actually be able to see the birth of Eldfell in 1973 and the indomitable spirit of the townspeople, who refused to let a volcano change their lifestyle. A child’s library book and its wonderfully vivid photographs would etch Vestmannaeyjar into my memory forevermore, but The Heimaey Eruption took me there, if only for 30 minutes.

“How amazing it would have been to have actually seen footage of the Tambora eruption of 1816 or indeed Krakatoa in 1883 – two eruptions that changed the world forever.”

*****

Still To Come On World On Film

Explorations into topics in and around the concept of film and the world it brings into your living room and the main series of reviews taking us to countries starting with ‘B’ begins with a tale of repressed sexuality, inner torment and discrimination in the Bahaman drama Float. All this and more in the upcoming weeks when World On Film continues.