Going Nowhere

High up in the Colombian Andes, a squad of soldiers manning a remote mountain bunker mysteriously all go missing. Believing their disappearance to be the work of the enemy guerrilla, base command sends another squad to investigate. However, the new arrivals soon find themselves unwittingly re-enacting the events leading up to their predecessor’s fate and it may not be the work of enemy agents.

The Squad

(2011) Written by Tania Cardenas and Jaime Osorio Marquez Directed by Jaime Osorio Marquez

(You’ll find a trailer at the bottom of last week’s post)

“Haven’t you realized it yet? There’s nobody out there! The only murderers are us, goddammit!”

Fear and hatred keep the wheel of conflict turning in Jaime Osorio Marquez’s claustrophobic horror-thriller, ‘The Squad’.

The above quote may seem to give away the film’s twist, but The Squad, sitting somewhere between horror and claustrophobic thriller, is a dark tale that will keep you guessing until the end. Taken as horror, it’s a story that benefits from director Jaime Osorio Marquez’s solid understanding that invoking the paranormal effectively benefits from the ‘less is more’ approach. This is not a man interested in cheap thrills. In fact, some viewers will question whether or not there really is a paranormal element to the film, given that it flirts with, but never conclusively states, an otherworldly force behind the drama. The most obvious example, and I will try to avoid spoilers, is the soldiers’ discovery of an old woman seemingly kept prisoner by their missing comrades. Speculation turns to fear when she is accused first of being a guerrilla spy, then an unfortunate local caught up in the country’s perpetual civil war, and then a witch – in any event the source of all the misery that befalls anyone cursed with entering the bunker. Marquez walks a fine line with all three possibilities, and gives just enough circumstantial evidence to allow the viewer to conclude that any one of them might be true.

However, since The Squad is so Spartan with its horror elements, it is predominantly a thriller about claustrophobia and fear in general. The war has completely polarised both sides of the conflict, and so the only dimensions of character among the soldiers we meet range between the aggressive, bullying nationalists and the moderates forced into a military environment they have no taste for, yet they too have no sympathy for the other side. It’s probably the most important thing to understand about the citizens of any country where national service is mandatory.

The film explores the way in which perpetual civil war has enslaved the mind and terrorised the soul in modern-day Columbia.

Add to this a deep sense of battle-weariness that the characters seem almost to breathe out from the very first scene. Although the narrative is entirely confined to the isolated Colombian outpost, lines of dialogue make it clear that this is simply the latest in a long line of engagements with the enemy. In peacetime, we often have trouble wondering how certain people are able to commit certain acts, and in The Squad, the elastic has already been stretched a good way for everyone involved. This, we are being told, is what it means to live amidst civil war.

Then the story actually begins and, after a quietly tense sequence in which the characters survey their surroundings, the screws start to be tightened even further. In many ways, The Squad is a base-under-siege film, both figuratively and literally. Visually, Marquez could not have chosen a more perfect location: it really is a bunker high up on a mountain somewhere, where the fog is so frequent that venturing in any direction will make you hopelessly lost if you’re lucky. The weather itself is a mental and physical barrier. All of which only helps make the ‘siege’ very much the cabin fever variety, taken to new heights by human weakness and paranoia. Already convinced they are under attack by guerrilla forces that always seem to be one step ahead of them, the unraveling of self-control for each beleaguered soldier seems only a matter of time. Yet as indicated earlier, there may be other forces at work.

“In peacetime, we often have trouble wondering how certain people are able to commit certain acts, and in The Squad, the elastic has already been stretched a good way for everyone involved.”

The sudden appearance of a woman who may or may not be in league with forces beyond human understanding throws a genre curve ball in what is predominantly a more down-to-earth and visceral base-under-siege film.

I couldn’t help but be strongly reminded of the in-many-ways-similar Korean horror-thriller Antarctic Journal, where a group of initially optimistic team of scientists attempt to be the first Koreans to reach the South Pole. There, writer/director Yim Pil-Sung similarly tries to offer both mundane and supernatural reasons for the group’s ultimate descent into madness and murder, so much so that he almost makes two different films running concurrently, and the whole doesn’t quite come together. Marquez is clearly the more adept at weaving the seemingly real with the seemingly unreal – perhaps because his main commentary is upon the prolonged effects of war on the psyche, especially when cornered. And yet in many ways, I find Antarctic Journal the more enjoyable film for all its faults.

Perhaps The Squad is too claustrophobic. Its protagonists, seemingly doomed to begin with, make the transition from ‘bad’ to ‘worse’ rather than Antarctic Journal’s ‘good’ to ‘bad’. We are thrown into the tension almost immediately, and when characters aren’t descending into madness, they are sniping at each other or making intense declarations of family loyalty. The true protagonists of the story are helpless from the outset, dominated by their unstable, aggressive and wholly unpleasant colleagues. Add to this an ongoing barrage of tight close-ups, washed-out colour and a very confined set, and there really isn’t room to breathe in The Squad. On paper, the almost Blair Witch-like approach should work well, but you can have too much of a good thing.

Excellent and atmospheric location choices help overcome some of the film’s lack of thematic coherence.

And perhaps the imbalance of the supernatural and the more down-to-earth brutality of the situation is another factor. If the film is allegory for the horrors of war through the use of supernatural elements – as John Carpenter’s The Thing is allegory for Antarctica-as-blue-collar-dystopia via sci-fi elements – then it doesn’t go far enough to work as allegory. Or to put it another way, while I applaud Marquez’s carefully-judged use of the supernatural (if, again, that’s what it is – and it’s up to the viewer to decide this) for the purposes of intelligently-made horror, there’s too little of it to work as a symbol of real-world psychological fear. Equally, since The Squad is therefore mostly a real-world study of human madness, that weighty discourse is derailed somewhat by occasionally saying ‘Hey, maybe these guys are being manipulated by forces beyond their understanding.’ This is where Antarctic Journal also ultimately fails: film-makers not deciding clearly enough as to what their story is ultimately about.

Which is a shame, as there are certainly a lot of interesting ideas in The Squad and a location setting that was absolutely made for horror. Then again, if true horror is human behaviour, then those Colombian mountains have likely already told that story many times over the years. While the film lacks clarity in some areas, not even the cold blanket of the fog can enshroud the utter senselessness of a never-ending conflict that exists now only to consume man until nothing but his fear-stained face, frozen in death, remains. If the film-maker somehow lost his way slightly in getting his story across, there is a certain irony in the fact that his characters – and the real-world analogues upon which they are based – are so deep within their society’s conflict that they are fated only to disappear without trace, like the lost people of whom they came in search.

*****

Next Time

We travel to the remote island archipelago of Comoros and discover how the locals cope with the country’s massive brain-drain in its very first film, The Ylang Ylang Residence. Plus: how to turn a real-life tragedy into a cheap melodrama. Air disasters and asinine production choices in the Ethiopian farce Comoros – next time on World On Film.

Are You Sitting Comfortably? Part II

July 2012 saw the 16th edition of Pifan, or the Puchon International Film Festival, held annually in Bucheon, South Korea. I was there and you can read about the first half of my experiences in the previous post. Here, then, is the second half.

I’m sure it would surprise precisely no-one that a Korean international film festival is principally for Koreans. Even the Busan International Film Festival, the largest event of its kind in Asia, makes little more than a perfunctory effort to provide English to international visitors most of the time. I still haven’t forgotten the debacular mockery inflicted upon non-industry ticket purchasers at BIFF 2011, forced, thanks to the virtual impossibility it was to purchase online, to be herded like sheep along a rubber-ribboned maze toward a hastily-erected festival ticket booth outside the world’s largest department store only to be told the tickets had already been snapped up by everyone who’d arrived 30 minutes earlier. “Wow, thank you BIFF for selling 80% of the tickets online to everyone in the film industry and local government officials who probably won’t even turn up – not to mention relocating the festival to one single city block so this ocean of human slave puppets can fight like dogs for jacked-up hotel prices before standing in a queue on the street full of frustration and broken promises. This couldn’t be any more awesome even if I painted my nose red and let you pelt me with wet sponges – which, by the way, I completely deserve at this point.” Meanwhile, darting around the line of disillusioned faces like bright red sheepdogs, barked a zig-zagging group of festival volunteers wielding portable whiteboards onto which were scribbled a bizarre series of numbers possibly denoting how many dumb suckers were letting themselves be robbed of their dignity, but were in fact a rapidly-growing list of number codes for all the films selling out before you reached the booth. None of which was explained in English, and so became a time experiment wherein one determines how long it takes each mystified member of the cattle run for the penny to drop.

I’m sure it would surprise precisely no-one that a Korean international film festival is principally for Koreans. Even the Busan International Film Festival, the largest event of its kind in Asia, makes little more than a perfunctory effort to provide English to international visitors most of the time. I still haven’t forgotten the debacular mockery inflicted upon non-industry ticket purchasers at BIFF 2011, forced, thanks to the virtual impossibility it was to purchase online, to be herded like sheep along a rubber-ribboned maze toward a hastily-erected festival ticket booth outside the world’s largest department store only to be told the tickets had already been snapped up by everyone who’d arrived 30 minutes earlier. “Wow, thank you BIFF for selling 80% of the tickets online to everyone in the film industry and local government officials who probably won’t even turn up – not to mention relocating the festival to one single city block so this ocean of human slave puppets can fight like dogs for jacked-up hotel prices before standing in a queue on the street full of frustration and broken promises. This couldn’t be any more awesome even if I painted my nose red and let you pelt me with wet sponges – which, by the way, I completely deserve at this point.” Meanwhile, darting around the line of disillusioned faces like bright red sheepdogs, barked a zig-zagging group of festival volunteers wielding portable whiteboards onto which were scribbled a bizarre series of numbers possibly denoting how many dumb suckers were letting themselves be robbed of their dignity, but were in fact a rapidly-growing list of number codes for all the films selling out before you reached the booth. None of which was explained in English, and so became a time experiment wherein one determines how long it takes each mystified member of the cattle run for the penny to drop.

“This couldn’t be any more awesome even if I painted my nose red and let you pelt me with wet sponges – which, by the way, I completely deserve at this point.”

And again, this is the biggest film festival in Asia. It’s meant to be a big-name brand event designed to attract niche tourism. The more diminutive and less-funded Pifan, meanwhile, can be forgiven for lacking many of the needed resources, not least the ability to pave the streets next to the venues. Not only can the regular masses actually purchase tickets online, but also the staff is actually trying to make it possible for them to enjoy themselves. How else to explain BIFF’s red-shirted counterparts actually walking around with bilingual signage, or the fact that I was at one point assigned a personal interpreter so that I could enjoy a post-screening Q&A session?

Pifan is also trying to make a big name for itself, evidenced by the foreign film-makers and press I met there, and needs to be properly bilingual if only to draw that kind of crowd. I apparently cut an incongruous figure, being asked three times if I were “industry or press”, as though those were the only two options. Sure, there’s this blog, and I did act in a short film recently, but that wasn’t the point. I was there as an enthusiast. I can’t have been the only one. To me, international film festivals are an incredibly important service, offering average citizens a (relatively) rare chance to see something beyond the strong-armed monopoly of mainstream cinema. For half the price of a normal ticket.

Ironically, the mainstream played a much larger role in the rest of my Pifan experience, to mixed results.

The Shining

(1980) Written & Directed by Stanley Kubrick

“When something happens, it can leave a trace of itself behind. I think a lot of things happened right here in this particular hotel over the years. And not all of ’em was good.”

Yes, I know – surely Stephen King wrote The Shining? Not this version he didn’t. King’s celebrated novel tells the story of a recovering alcoholic with anger management issues trying desperately to do the right thing and hold on to his damaged family by accepting the winter caretaker’s job at remote Colorado mountain lodge, the Overlook, as a last-ditch chance to avoid poverty. However, his efforts to stay on the straight and narrow are completely disrupted by the hotel’s evil spirit, its power accentuated by his telepathic son. The story is a strong blend of the supernatural and King’s usual exploration of blue-collar family relationships put to the test by forces beyond their control.

Contrast this with The Shining, a story about a barely-under-control malcontent seemingly saddled with a family he doesn’t especially want taking a job at the Overlook in order to gain the peace and quiet he needs to write a novel. Quick to begin losing his sanity long before the hotel asserts its malign influence, this version of the character is the principle catalyst for the Amityville Horror-style rampage that follows, with the Overlook simply tapping into a pre-existing madness. While wrapped in similar packaging, the two stories could not be more different – and the above comparison barely scratches the surface of their asymmetry. Stephen King clearly agreed with this assessment, overseeing a televised adaptation of his book in 1997, which is, aside from the story’s climax, about as faithful as a four-hour miniseries can be.

“This is a man who could have made a film about the Yellow Pages and we’d all want to see it.”

And yet while The Shining both largely dismisses and tramples upon the source material, it has the kind of unsettling and claustrophobic atmosphere coupled with the trademark eye-catching cinematography and editing that make anything Stanley Kubrick does so compelling. This is a man who could have made a film about the Yellow Pages and we’d all want to see it. Add to this yet another force of nature in front of the lens in the form of Jack Nicholson, very much at the top of his game and with the kind of presence that superglues your eyes to the screen, almost afraid to see what he’ll do next. Jack Nicholson could perform the Yellow Pages and we’d all want to see it. Those of us still clinging to the remaining tatters of King’s original story have little choice but to declare him completely miscast as Jack Torrance – not because of One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest (I for one haven’t even seen it) – but because every nuance of his performance, every arched eyebrow, every glint in his eye and every cynical tone drawling from his lips telegraphs Torrance’s impending madness like flashing, ten-foot-high neon. Yet none of those people would actually say what he was doing on screen wasn’t interesting.

Then there’s that softly-disconcerting soundtrack by Wendy Carlos and Rachel Elkind intermingled with various classic found tracks of a different lifetime, the imposingly-dark brown visage of the Timberline Lodge-as-Overlook, the threatening majesty of Mt. Hood, and a whole raft of elements that make this psychological base-under-siege melodrama work so well. For King fans, it is an exercise in doublethink, where they must put aside the author’s middle American melodrama and enter Kubrick’s realm without any preconceptions. Imagine if King’s version of ‘The Shining’ was a true account of events, and The Shining is the fast-paced Hollywood thriller based on those events. Except that Kubrick was clearly seeing the story through an entirely different lens.

Room 237

(2012) Directed by Rodney Ascher

If you thought ‘The Shining’ ought to consist mostly of this opening shot over and over again, ‘Room 237’ is the documentary for you.

So imagine that you’re a fan of The Shining, and you’ve watched it over and over again in the 32 years since it was released. You know every line of dialogue, you’ve consciously studied every one of the set props, you’ve been struck by the symmetry of cross-fading shots, and you’ve stared at that opening shot of a helicopter flight across Lake St. Mary until the idea of it being just a helicopter flight across Lake St. Mary is patently absurd. Because you know Stanley Kubrick. Stanley Kubrick the perfectionist auteur who once made Shelley Duvall swing a baseball bat over and over again until she lost her mind. Stanley Kubrick the obsessive-compulsive director who turned a 17-week shoot into a 46-week shoot and had Jack Nicholson demolish 60 doors for the “Here’s Johnny!” scene. This is not a man who does anything by accident. Every one of those Spherical 35mm frames has been planned to the Nth degree.

All of which you know, of course. Now imagine someone decided to shoot a documentary where uber-fans like yourself get to discuss all the hidden meanings and themes you know are what Kubrick was aiming for.

This is Room 237, a brand-new celebration to deconstruction peopled by individuals who know The Shining better than you do and possibly Kubrick himself. Some of the theories aren’t new: there is long-debated good evidence to suggest The Shining is in part recreating the destruction of the Native Americans by the “weak” white interloper, likewise the Holocaust allegory has been around equally as long, and ‘everyone’ knows the film is one massive allegory for Kubrick’s tension-filled assignment to fake footage of the Moon Landing for NASA. The ‘Obvious When Pointed Out’ file is well-explored also, in particular Kubrick’s tendency to mess with a passive movie-going audience with visual non-sequiturs and provocative props just outside the first-time viewer’s field of vision. The suggestion that Kubrick’s face has been superimposed into the clouds in the opening sequence however, that a standing ladder is meant to mirror part of the hotel’s exterior architecture, or that if you play the film forwards and backwards simultaneously, you’ll see all kinds of intentional thematic symmetry, definitely belongs at the speculative end of the pool. However, the various attempts to reach beyond reasonable lengths at the film’s discourse are welcomingly absurd interludes between the more serious – and in all likelihood more accurate – interpretations of Kubrick’s work. Ascher neither wants nor expects us to take all of Room 237 seriously, and in so doing ensures his documentary doesn’t bear all the stomach-tightening hallmarks of an Alex Jones conspiracy piece.

Consequently, what you won’t find in this film are musings from cast and crew, or indeed what they thought The Shining was about. For that, Vivian Kubrick’s 35-minute on-set short is still the best bet. Room 237 is a light academic paean to the film which spawned it, and for fans, is definitely worth a look. Everyone else will probably wonder what the fuss is all about.

3-2-1…Frankie Go Boom

(2012) Written & Directed by Jordan Roberts

The Pifan Daily, freely available during the festival. Apparently I missed the meeting where the word ‘daily’ was redefined to mean ‘twice-only’.

Time now to unzip our parachutes and float down to Dick Joke Island, where relative newcomer to film Jordan Roberts, perhaps in a bid to prove our species really did evolve from primates, clearly believed the market needed another 90 minutes of genital-related humour, now that Harold & Kumar have annoyingly grown up. The infantile Frankie Go Boom also inflicts upon the viewer that other ‘essential’ element of frat-boy comedy, the intensely annoying main character one is supposed to find loveable and hilarious. Twenty years ago, it was the disturbing mental case brought to life by Bill Murray in What About Bob?; today, it’s Chris O’Dowd donning an American accent to play the sociopathic Bruce, a young man oblivious to the lifelong psychological trauma he has inflicted upon his younger brother Frankie by filming every one of his most compromising moments and screening them to a giggling public – a practice all the more destructive in the age of file-swapping and broadband. Add the obligatory ‘touching’ romance, ‘crazy’ and unsympathetic family and Ron Perlman sacrificing the last vestige of his dignity, and presto: another tedious trek through the teen mire. You know, maybe we could get Scorsese interested in that Yellow Pages idea.

Puchon Choice Short 1

Another collection of short films, of which the quality averaged slightly lower than last time. Things get off to an uneven start with the Korean black comedy, The Bad Earth, where office employee Seung Bum puts himself at odds with his co-workers by refusing to clap along during company presentations and after-hours reverie. Clapping, as Seung Bum, firmly believes, is in fact an insidious form of alien virus that makes the human race ripe for the plucking. I will credit film-maker Yoo Seung Jo for adding to the shallow waters of sci-fi in Korea, a genre the country has historically had little reason to explore. However, the story’s premise is a little too ludicrous to be taken seriously, even if Seung Bum just might have good reason for believing it.

Very little credit, meanwhile, should be afforded Han Ji Hye, who in The Birth Of A Hero quite shamelessly takes the ‘Rabbit of Caerbannog’ scene from Monty Python & The Holy Grail and transposes it onto a rooftop in downtown Seoul. The idea that he might possibly be ignorant of this hallowed source material evaporated once the otherwise docile white rabbit began flying through air towards its victims and gouging out their necks in precisely the same manner. If Han is lauded as a master of surrealist cinema after this unbelievable cribbing, he deserves to be fed to the Legendary Black Beast of Aaaaarrrrrrggghhh!

Quality began to reassert itself at this point to the unusual Korean stop-motion animated short, Giant Room, in which a man rents out a space in a strange, colourless building. Told explicitly by the landlord not to enter the room marked “Do not enter this door”, the newcomer ignores the warning to his great peril. It’s always hard not to be impressed by the work put into old-style animation – just getting 10 minutes of useable material must have taken months. The claustrophobic miniature sets are also well-designed, and the decision to abstain from dialogue a good complement. Hopefully this is not the only feature we will see from Kim Si Jin.

“I will credit film-maker Yoo Seung Jo for adding to the shallow waters of sci-fi in Korea, a genre the country has historically had little reason to explore.”

The drama finally moved overseas at this point for the dystopian US horror, Meat Me In Pleasantville. It is the near future, where overpopulation has finally used up all of the world’s meat reserves, causing the federal government to make cannibalism legal. Inevitably, some citizens agree with this decision more than others, particularly dependent upon who is at the other end of a meat cleaver at any given time. As the Pleasantville population’s taste for human flesh turns them all into murderous zombies, a father and his daughter fight to escape, though they too are only human. Fans of slasher horror will not be swayed too much by the gore of Greg Hanson and Casey Regan’s half-hour kill-fest, though the real-world basis for the story would, I think, amuse George Romero. It’s a little difficult to imagine a government making cannibalism legal, or that a population would ever go through with it, but anyone who thinks that humans couldn’t acquire a taste for their own flesh – or want to keep eating it after that first bite – ought to read the real-world story of one Alexander Pearce. Unfortunately, both acting and dialogue fail to match the worthiness of the concept, making Meat Me In Pleasantville a little hard to digest.

The theme of vampirism returns in fellow US horror short, The Local’s Bite, where a young woman traveling home via ski lift after a night out with friends tries to evade a stalker. Film-maker Scott Upshur puts the unusual transport system common to his local town to good use in this suspenseful drama, which squanders its build-up at the last moment for unrealistic fantasy in the name of plot twists and humour. And again, the acting is highly variable, with the horribly wooden appearance of a clearly real-world ski lift operator struggling like mad to deliver a single line. However, Upshur’s talent for rising tension, good location choices and decent editing cannot be ignored, and those are the areas he should focus upon in the future.

It was the final entry in the collection, Antoine & The Heroes, that proved most enjoyable. In the French comedy-pastiche, B-grade film obsessive Antoine is forced to choose between two simultaneously-screening films at his local cinema complex, each showing his two favourite screen stars and each on their final showing. Unable to decide, Antoine decides to watch both, dashing back and forth between cinemas to catch the highlights. Hailing from the days when kung-fu couldn’t be achieved without a funky disco track and heroines screamed and screamed without ever needing Vicks Vapodrops, cool cat Jim Kelly beats up the baddies without messing up his bouffant in his latest piece of kung-fu cinema, while long blonde silver screen star Angela Steele dodges groping zombies in her new horror blockbuster. At first, Antoine manages to alternate between the two spectaculars with ease, but a small accident results in the blending of realities, films and genres to comedic effect. The best thing about this film is Patrick Bagot’s excellent pastiche of 70’s style kung-fu and B-grade horror – both very much in-vogue during that hirsute decade – realized by some great acting, costumes, sets, and appropriate period soundtracks. Anyone with childhood memories of 70s pop culture will feel more than a little nostalgic by the end of Antoine & The Heroes, reminded of why it was all so much fun – even if it does look ridiculous four decades on.

*****

Next Time

“From all directions They come, caring nothing for demarcation lines between man and motor. On every pavement, in every street, across every veranda, and through every backyard, they cover the town in a scuttling sea of red.”

World On Film pays a visit to Christmas Island and comes face to face with its most colourful inhabitants – a sidestep from the usual film fare, next time.

Are You Sitting Comfortably? Part I

In this edition of World On Film, I look back over my visit to the recent Puchon International Fantastic Film Festival (Pifan), and give quick takes on the screenings I managed to catch.

In this edition of World On Film, I look back over my visit to the recent Puchon International Fantastic Film Festival (Pifan), and give quick takes on the screenings I managed to catch.

I’d been wanting to catch Pifan for a few years now, but always somehow managed to forget when it was on. However, after the complete debacle that was BIFF 2011, it was time to get serious about it. For those wondering, Pifan takes place in Bucheon, a city in the Korean province of Gyeonggi, located roughly halfway between Seoul and Incheon. There are eight categories, including World Fantastic Cinema, Ani-Fanta, and Fantastic Short Films. Only one category, Puchon Choice, is competitive, with the winners being screened on the final weekend of the festival. This is Pifan’s 16th year, making it almost as long as its counterpart in Busan.

Physically-speaking, Pifan is smaller than BIFF, and organised much the way BIFF used to be, ie – with screenings sanely distributed across in a number of cinemas throughout downtown Bucheon with one particular venue, Puchon Square, at the centre. It has yet to become the almost industry-only event that is BIFF today, which in practical terms means the average joe can actually get tickets for this thing both online or by simply turning up to the ticket offices in timely fashion. There’s no insane queuing for hours, no giant department store you have to trek through with huskies just to reach a screening, nor the feeling that if you aren’t press or industry, you’re getting in everyone’s way.

On the flipside of this, Bucheon is hardly the most exciting city to hold a festival, the main street seems to be in a permanent state of construction, and the more modest department stores in which the cinemas are located don’t have the greatest selection of cuisine. On balance however, I had a very positive experience, so I aim to make the best of Pifan until it inevitably becomes so successful that getting tickets for screenings will become as difficult as convincing Adam Sandler to stop making movies.

I managed to catch something from most of the categories mentioned during my visit. Here is what I saw:

Hard Labor

(Brazil, 2011) Written & Directed by Marco Dutra and Juliana Rojas

Sao Paolo housewife Helena is about to realise her dream of starting her own business in the form of a neighborhood supermarket. Yet just as she is about to sign the papers for the property lease, her husband, Otavio, is fired from his job as an insurance executive after ten years’ faithful service. However, the couple decides to risk the investment and the store opens, though for some reason, business just doesn’t seem to be taking off, seemingly in direct proportion with Otavio’s failure to find work and mounting alienation from the family. As an increasingly-stressed Helena struggles to hold everything together, she finds her attention drawn to a crumbling supermarket wall and wonders whether it might hold the answers to her problems.

“There’s no insane queuing for hours, no giant department store you have to trek through with huskies just to reach a screening, nor the feeling that if you aren’t press or industry, you’re getting in everyone’s way.”

For much of its screen time, Hard Labor is more a drama about family breakdown than it is a horror movie, which is especially important for horror fans to bear in mind when going into it. Although there are definitely supernatural elements to the story, they are there to be allegorical, to act as a catalyst for the primarily human conflict which takes place. The problem for me at least is that neither of these elements quite reach the crescendo they could have had and there is a little too much stillness throughout. It isn’t really until the final scene that I felt the two strands really came together, but that does mean that Hard Labor has a satisfying ending. Anyone who’s ever had to face long-term unemployment through no fault of their own will appreciate the film’s central message that to get by in this ultra-competitive world, you sometimes have to unleash the inner animal. Good casting choices, lighting, and set construction also help to push Hard Labor over the line, along with the occasional dash of dark humour.

The Heineken Kidnapping

(Netherlands, 2011) Directed by Maarten Treurniet Written by Kees van Beijnum & Maarten Treurniet

Rutger Hauer stars in Maarten Treurniet’s interpretation of ‘The Heineken Kidnapping’ (image: Pifan Daily)

As its title suggests, The Heineken Kidnapping retells the true-life incident when in 1982, Alfred Heineken, then-president of the family business, was kidnapped by four individuals for the ransom money. Based loosely on the events as reported by Peter R. de Vries, the film focuses on the careful planning, abduction, and aftermath of the event, in which the traumatised Heineken struggles to cope with his imprisonment as well as fight various legal loopholes in order to bring the criminals to justice.

Since its release, the film has been criticised for playing fast and loose with the facts of the case, as well as glossing over the highly meticulous planning the four young men undertook before making their move. I therefore probably had the advantage of ignorance, in that I had never heard of the kidnapping before, and simply took what I saw at face value. To me, The Heineken Kidnapping was a fairly compelling crime drama with a strong cast, most notably in the form of Reinout Scholten van Aschat as the psychopathic young Rem Humbrechts, for whom the operation is as much for sadistic pleasure as it is for financial gain. Meanwhile Rutger Hauer turns in a strong and sympathetic performance as Alfred Heineken himself, which, given that the audience is being asked to care about the plight of an extremely wealthy adulterer, is a testament to the actor’s longstanding talent. Those more familiar with the source material may feel differently, but for me at least, The Heineken Kidnapping was an enjoyable example of Dutch cinema, and proved to be one of the more talked-about entries at Pifan – at least going by some of the people I met during my visit.

Extraterrestrial

(Spain, 2011) Written & Directed by Nacho Vigolondo

When a series of flying saucers begin hovering over the cities of Spain, most of the population takes to the hills. However, for Julio, a young advertising artist in Cantabria, the more pressing concern is to stay as close to Julia, the girl of his dreams, in whose apartment he has just spent a passionate evening. Unfortunately, matters are complicated by the presence of Julia’s nosy next-door neighbour and the return of her longtime boyfriend. But Julio will do anything to be with the girl he loves – even if that means making up a convoluted series of lies about an alien invasion – just to stay on the premises.

“At its core, Extraterrestrial is really a pretty conventional romance-comedy that hits all the usual notes its well-worn formula demands.”

With dramatic shots of a saucer hovering above urban skyscrapers and dire warnings by the authorities to stay out of harm’s way, one could be forgiven for thinking that Extraterrestrial might be another District 9. However, as with Hard Labor, the fantastical elements of the script serve merely to push a group of individuals together into a confined space and add colour to the background. At its core, Extraterrestrial is really a pretty conventional romance-comedy that hits all the usual notes its well-worn formula demands, and the unusual setting little more than an elaborate misdirection. That said, it is a pleasing enough 90 minutes with some enjoyable humour, and Julian Villagran makes for an unconventional romantic lead. Nonetheless, would-be viewers are advised to set their phasers on ‘low expectations’ for the best result.

Spellbound (aka Chilling Romance)

(South Korea, 2011) Written & Directed by Hwang In-ho

Yuri, a shy young woman living in Seoul, is haunted by the ghost of her dead schoolfriend who lost her life during an ill-fated class excursion. Desperate for human company, Yuri has resigned herself to the fact that she will never enjoy close friendships or romance as long as a malignant ghost frightens away anyone who comes near. Hope comes in the form of Jogu, a wealthy stage magician who becomes intrigued by Yuri after he hires her for his illusionist act. With everyone else running from her in fear, will Jogu’s affection for his star performer be strong enough to overcome resistance from the Other Side?

I’d been warned before the screening began that Spellbound was something of a corn-fest, and by the end credits, felt so overdosed on saccharine, I nearly checked myself into a medical clinic for a diabetes test. In a country where clichéd melodrama is so popular it’s a major international export, Spellbound does not stand out from the crowd. With every passing minute came cliché after tired cliché about ill-fated romance, and every stomach-churning line about love and dreams meticulously welded to a truly nauseatingly-twee soundtrack had me twisting in my seat and groaning like an old man putting Viagra to use for the first time. If Extraterrestrial was formulaic, Spellbound was the formula, right down to the wise-cracking but experienced friends and sidekicks of the lead characters. All of which was so overwhelming that the horror element to the story, and raison d’etre for the whole situation was never adequately built up to be anything especially convincing and had me longing for the Dementors to float in on special dispensation from Azkaban and suck everyone’s souls into oblivion. Son Yeji gave a creditably agonised performance as the long-persecuted female lead, but frankly, the entire cast could have simply sat in a pool filled with corn syrup and elicited the same drippy performance. That, at least, would have been more honest.

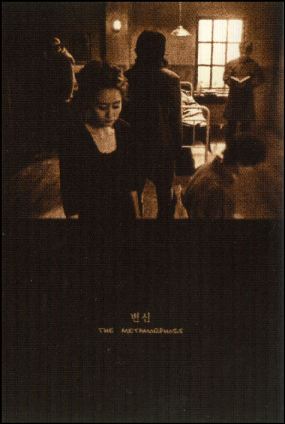

Fantastic Short Films 7

Postcard for the Korean short film ‘The Metamorphosis’, handed out to patrons as they entered the cinema for the ‘Fantastic Short Films 7’ collection.

The great thing about short film collections is that if one film proves awful, you don’t have to wait long for the next one. FSF7 however started strong, with the Korean entry Delayed, in which a young middle-aged woman waits patiently at a near-deserted train station for her husband to arrive. Yet as she strikes up a conversation with an inquisitive man claiming also be expecting an arrival, nothing seems to be quite as it appears. Cast and crew of this very moving short appeared live on stage at the end, where director Kim Dong-han explained his desire to connect lost souls with lost train stations. My thanks to the Pifan personal interpreter who sat with me during this unexpected bonus event!

Next up, the Japanese parody-pastiche Encounters, wherein two very good friends look for adventure in the countryside and find more than they bargain for with giant monsters roaming the streets thanks to the machinations of an evil professor. Shot entirely using plastic action figures and some deliberately wonky props and sets, Encounters is a tongue-in-cheek Godzilla-like comedy, complete with lame action sequences and bad dialogue. I’d like to think the English subtitles weren’t meant to be quite as poor as they were, but if so, mission accomplished!

“The quality then takes a serious nosedive with the unpleasant and forgettable Italian horror mish-mash, I’m Dead, and I certainly wished I’d been dead during the 17 minutes it screened.”

The quality then takes a serious nosedive with the unpleasant and forgettable Italian horror mish-mash, I’m Dead, and I certainly wished I’d been dead during the 17 minutes it screened. Two long-time friends out hiking in the forest suddenly find themselves kidnapped by a crazed religious fanatic who begins torturing them in his secret underground lair, replete with bad lighting, corpses and handy tunnel system. The pointless and gruesome tale offers no depth in terms of the reasons behind the mad psychopath, nor indeed the ridiculous twist at the end. Which is an interesting coincidence, because I can offer no reason why anyone should watch it.

The macabre continues – though in a very different style – in the form of the Korean silent film, The Metamorphosis, a shadowy sepia affair with the disconcerting performances of Eraserhead and the visual echoes of Nosferatu. Claustrophobic static shots combine with heavy industrial clanking and retro white-on-black dialogue text inserts to tell the story of a family beset by vampirism. In truth, it’s a great example of style over substance that adds little storywise to the genre and comes close at one point to mobs with burning torches. Yet it’s the style that proves the most compelling here, so that while I’m not entirely sure what I saw, it was impossible to take my eyes off the screen. There are plenty of music videos like that.

Rounding out the collection was the light-hearted martial arts/crime spectacular, Pandora, in which taekwondo trainee Jeong Hun arrives in the city of Chungju for a performance, only to accidentally switch his cell phone with that of a man on the run from a gang intent on seizing the secrets the identical device contains. The film is a fairly unremarkable, reasonably-paced runaround that could not possibly satisfy fans of martial arts films, offering nothing new by way of story or visuals. When a story is full of clichés that have been done better elsewhere, you have to wonder who the intended audience really is. As a 30-minute romp in a film festival, Pandora is sufficient eye candy, but on its own, it swims in crowded waters.

*****

Next Time

The second half of my Pifan retrospective. I finally get to see Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining on the big screen, watch the over-reaching new documentary about the very same, entitled Room 237, find myself underwhelmed by the new Harold & Kumar-style American feature, 3-2-1…Frankie Go Boom and sit through another short film collection with mixed results. That’s World On Film next time.

Deliverance

So far in this series, we’ve explored the triumph of science in the South Pole, looking at the ways in which Antarctica has been a frontier for advancing the human endeavour and a deeper understanding of our planet, both in fiction and genuine footage of a famous expedition. Time for a change of pace now. Antarctica isn’t a place of eternal wonder for all who have worked there, or, as with Virus: Day Of Resurrection last week, a land where the nations of the world put aside their differences for the greater good. Behind every polar expedition there were the grunts – the blue collar workers who carried out the actual hard work and fixed things when they broke down. Inevitably, their Antarctica would be far less glamourous.

Neither is Antarctica universally seen as simply a giant laboratory for altruistic science. Even during Byrd’s time, there were many who saw the South Pole as new land to conquer, its position more of strategic than scientific value. The U.S. Antarctic Expedition of 1939-1941 had as much to do with establishing an American presence there as it did exploration. Today, when the major nations have indeed become a permanent fixture at McMurdo and other base camps, many who work there simply see it as a job – one they are even taxed for – and certainly bound by government and commercial interests just as with anywhere else. Add to that the fact that Antarctica is a hostile environment far from most of the basic comforts, where holding onto one’s sanity is a very real concern, and where one is frequently trapped for months on end with people they don’t necessarily like, and the rose-coloured lens through which the Byrds of the world viewed Antarctica become mottled.

This rather sobering perspective forms the ethos for John Carpenter’s excellent remake of The Thing From Another World, itself an adaptation of the novella ‘Who Goes There?’ by John W. Campbell Jr, published in the August 1938 edition of America’s longest-running science fiction magazine, Astounding Stories. In terms of cinema, it is Carpenter’s version of the tale that has most famously – and most effectively – depicted the blue collar perspective on Antarctica, using the science fiction and horror of the novella as allegory for the difficulties they face there.

The Thing

(1982) Screenplay by Bill Lancaster Directed by John Carpenter

(You can find a trailer at the bottom of last week’s post)

“Somebody in this camp ain’t what he appears to be. Right now that may be one or two of us. By spring, it could be all of us.”

Far from being a wondrous, unexplored outpost of Earth, the Antarctica of ‘The Thing’ is a dangerous and claustrophobic wilderness.

In the story, a group of scientists stationed at an American Antarctic base encounter an alien life form able to change its shape into that of the host body it has infected. Suspicion turns to paranoia as it quickly becomes apparent that no-one is who he seems. As the fight for survival turns the base personnel against each other, the greater cost is soon realised: if the thing were ever to make contact with the outside world, all of humanity would be destroyed within three years.

One of the ways in which The Thing succeeds so well in its genre is the careful minimalism of Lancaster’s script and Carpenter’s direction. At no point do we ever truly learn, for example, of the alien’s origin, the reason it crashed to Earth, why it landed in Antarctica, whether or not it is sentient, or indeed its true objective in taking over other life forms. Even the title of the film makes this ambiguity plain and if anything, underscores not only the mystery, but the anti-intellectualism of the base personnel: it is simply a threat to be dealt with, its extra-terrestrial identity more of an irritation than of interest. Unsurprisingly, any survivors might argue that its lethality renders any such disinterest entirely justified.

“Behind every polar expedition there were the grunts – the blue collar workers who carried out the actual hard work and fixed things when they broke down. Inevitably, their Antarctica would be far less glamourous.”

Nor indeed do we learn a great deal about the characters themselves or the purpose of their presence in Antarctica. There seems little, if any, significant research being conducted there and what work does take place is of supreme indifference to the staff. They are simply filling out a contract and counting down the days to its completion. The base staff in turn appear merely to tolerate each other akin to Adamsian office workers, albeit office workers forced to see their colleagues round the clock and to the exclusion of all else. Conversation is stifled by familiarity, contempt, and lack of stimulus (until the drama begins) and entertainment takes the form of alcohol, months-old off-air television recordings, ping-pong, and a well-worn record collection.

Embodying this seemingly-pointless, isolated existence is the classic antihero and main character of R.J. MacReady, very convincingly played by a young and hirsute Kurt Russell. The perpetually Stetson-wearing, hard-bitten and cynical time-server is purposely constructed as a cowboy of the modern age, able to fit quite easily into the seedy saloon bar of some Tombstone-like frontier town of over a century ago. The anti-intellectualism inherent in MacReady and his fellows is expertly summed up in an early scene where his response to losing at computer chess is to pour the remains of his whisky into its circuitry.

Explorations of the Norwegian base suggest the inhabitants may have had good reason to reduce the local dog population.

The cynicism and mistrust is further exemplified and exacerbated by other common elements of Antarctic life. Not only is technology seen to cause problems rather than solve them, but so too other nations – a far cry from the spirit of global fellowship seen in Virus. It is the Norwegians – often derided by others in Antarctica for their prowess in polar climates (and derogatively dubbed ‘Swedes’ by the main character) – who bring the alien to the U.S. base, having failed ironically to deal with it. Even in Virus, it is the Norwegians who are quicker to succumb than their multinational counterparts. Elsewhere, in another role-reversal, an Alaskan malamute, typically used as a sled dog, is the initial carrier of the alien creature.

The Antarctica of The Thing is not the land of adventure and opportunity. Its snow-covered jagged mountains are uninviting, its rolling plains bleak and lifeless, and its terrain offering nothing but mortal danger. It is far from the warmth of civilisation, will quickly kill anyone who strays from their electric-powered shelters with its sub-zero temperatures, and the ground beneath harbours monsters who bring swift, painful oblivion. The ‘thing’ is the ultimate Antarctic allegory for the long-term resident – the near-unbeatable agent of death who threatens to rob them of their humanity, not with merciful swiftness, but by rotting them slowly from within. The South Pole is still the giant laboratory it has always been for those looking at the other end of the microscope: at the furthest frontier of civilisation, humans are unwittingly being tested to see how they fare in extreme conditions. In reality, British Columbia doubles for the frozen continent, but is visually no less convincing to all but perhaps the skilled geologist. The brooding atmosphere is strongly accentuated by Ennio Morricone’s evocative score, different in style from Carpenter’s own compositions and unsurprisingly smoother and more accomplished, yet still fitting quite well into the era of the early Halloweens and The Fog.

The veteran horror director had by this point established his expertise in suspense-filled, well-paced tales of the macabre. The two films mentioned above were both classic examples of highly-effective base-under-siege drama, and in The Thing, Carpenter finally takes the term to its most literal conclusion. The cold, functional, and labyrinthine Antarctic base we see in the film is a perfect counterpoint to the bleak perpetual winter of nothingness outside. The disillusioned denizens inside provide only a candle-flame of human warmth, serving not even enlightened self-interest, but simply the powers of inertia. This disillusion is Carpenter’s contribution to the story, with the original novella produced during the positivist golden era of Byrd-mania. As is typically the case, the remake shows the rising cynicism of the public since the time of the original, no longer so easily caught up in nationalist fervour.

“The Antarctica of The Thing is not the land of adventure and opportunity. Its snow-covered jagged mountains are uninviting, its rolling plains bleak and lifeless, and its terrain offering nothing but mortal danger.”

As the mysterious infection begins to spread, the protagonists discover that it may not be home-grown in origin.

Carpenter and Russell had already collaborated on the director’s earlier apocalyptic outing, Escape From New York, with the young star by now fully aware of what was required of him. Other standouts in the cast include Wilford Brimley as Blair, the scientist who realises no-one present should be allowed to get out alive, Keith David as disbelieving aggressor Childs, and Donald Moffat as Garry, the self-admitting ineffectual leader of the base. A great deal of credit at this point should also go to both Jed, the Alaskan malamute, and his trainer, who between them do an excellent job of creating the dog’s alien nature. Jed, who would go on to play the title character in White Fang, though obviously unaware of the script, is one of the best trained dogs in the business, his body language convincing the viewer of his alter-ego’s menace with every step.

Pushing the envelope for early-80s practical effects is master of gore Rob Bottin, who in The Thing really gives contemporary innards wizard Lucio Fulci a run for his money. Bottin, whose make-up effects work includes The Howling, Twilight Zone: The Movie and Total Recall, lived on set for over a year during the making of The Thing, working round the clock to create visuals that were so gruesome for the period that they polarised film critics worldwide. While from a modern perspective, the clunky movement and obvious puppetry of the alien invaders is evident, so too is the sheer amount of detail in their construction. They are still far more ‘solid’ than any CGI equivalent, and still just as horrific in their design, helped by the well-matched screeching sound design. It could be argued effectively that a number of sequences exist simply to serve the visual effects extravaganza and a more cerebral interpretation of alien metamorphosis might have been employed. The Thing, however, is not intended to be The Midwich Cuckoos, and thanks to good pacing, does not fall into a long, drawn-out visual-effects love-fest at the cost of a story, which is more than can be said for Fulci’s The Beyond of the same period. It’s probably also fair to say that time and familiarity have dulled the senses with my reading of the film, and its efforts seem tame compared to say, Rob Zombie’s Halloween II.

Kurt Russell as R.J. MacReady, the anti-intellectual, time-serving helicopter pilot given yet another reason to get the hell out of Antarctica.

The somewhat forgiving nature for old cinema and a healthy suspension of disbelief also help in areas where The Thing does not accurately depict Antarctic life, allegorical or otherwise. Compelling though his performance is, Kurt Russell’s cool cowboy image is more 80s action hero than Antarctic expedition pilot, likewise Childs and Garry fit the typical formula of antagonist and weak authority figure, while radio operator and Jeff Lynne lookalike contest runner-up Windows clearly went to the Crispin Glover school of ‘We’re All Going To Die, Man!’ acting. The easy availability of firearms and flame-throwers to all personnel, along with the high population of open-standing fuel drums also tends to stretch credulity, even before the coming of the Antarctic Treaty. It’s easy to hold up the extra-terrestrial element as justification for action-genre fantasy, but every story should still operate within its own internal logic. Nonetheless, the abundant weaponry and especially flamethrowers are used to satisfying effect, the latter proving especially critical in helping contain the alien menace. Dramatic license is well-served, and the film reaches the type of satisfying ending one would reasonably expect of its horror shoot-em-up credentials, indeed concluding in Carpenter’s signature open-ended dystopian fashion.

And it seems that the story is not over. In 2011, viewers will discover just what happened at the Norwegian base prior to the events of The Thing in a new prequel due for release at the end of the year. Only time will tell if the exercise worthwhile. In the meantime, I encourage interested parties to rediscover the flawed, but entertaining ‘original’ in all its blu-ray glory. I had occasion recently to do just this and found it held up extremely well. It needn’t wash away all that optimistic Antarctic fervour, but perhaps the last word should go to Mr. Campbell himself in this extract from Who Goes There? as the alien spacecraft is destroyed in a mass of flame:

Somehow in the blinding inferno we could see great hunched things, black bulks glowing, even so. They shed even the furious incandescence of the magnesium for a time. Those must have been the engines, we knew. Secrets going in a blazing glory -secrets that might have given Man the planets. Mysterious things that could lift and hurl that ship -and had soaked in the force of the Earth’s magnetic field.

The human adventure continues.

Further Reading

- Keep up to date with the latest news on the U.S. Antarctic program and the people who make it possible with the Antarctic Sun.

- Serious Thing enthusiasts might like to read Robert Meakin’s in-depth analysis of the film here.

- Learn more about today’s Antarctic program and meet the people who actually work there, as well as discovering how they view the place.

*****

Next Time

Antarctica, February 1953: The first year of Japan’s new Showa Station has drawn to a successful close. The expedition team depart from the base to make way for the relief crew, leaving 15 huskies remaining behind with a small supply of food to keep them nourished during the changeover. However, adverse weather conditions prevent landfall and the second expedition never arrives. The dogs are abandoned to their fate, forced to survive alone in the harsh, polar landscape. Antarctic Film Month concludes with the epic true story of Antarctica, when World On Film returns. Click below to see the original trailer.

Storm Warning

Dark skies overhead this week as the self-righteous are forced to reveal their darkest secrets in Stephen King’s miniseries Storm Of The Century.

Normally focused upon international cinema, this post forms part of World On Film’s break time between series. To find out what is upcoming over the next few weeks, please scroll to the bottom.

But now, we travel to the North American state of Maine – the fictional Maine, where savage clowns plague the dreams of the young and where cemeteries are more likely to bring back the dead than house them. Eleven years ago, I happened to discover Stephen King’s then-latest epic in the VCD section of Central, Hong Kong’s HMV, and it’s stayed with me ever since.

Storm Of The Century

(1999) Written by Stephen King Directed by Craig R. Baxley

“Born in lust, turn to dust. Born in sin, come on in!”

All hell breaks loose when a stranger visits the remote Maine community of Little Tall Island on a cold Winter’s day. As the biggest storm on record rolls over the town, a series of murders plague the community. All evidence points to the new arrival, who seems to know everyone’s darkest secrets. Powerless to stop him, the locals quickly learn that they will only see the last of Andre Linoge if they give him what he wants – the price for which may cost them their very souls.

The social fabric is torn apart and accusations fly as the townspeople are forced to bare their true nature to each other.

I have yet to pinpoint the moment in which prolific horror writer Stephen King became his own cabaret act, however it was most certainly long before Storm Of The Century, in many ways another ‘greatest hits’ package of King’s themes and stories. Again, we are presented with a cast of working-class Maine residents with dark – but entirely human – secrets lurking just beneath the veneer of their New England community spirit. Again, it is the presence of a dark figure from Christian mythology who upturns the shared lie of their ordered lives, offering the weakest a choice that will rob them of their humanity and for which the chief protagonists will rail against with righteous self-sacrifice. And again, it takes place in a sleepy town somewhere in between genuine Maine population centres creating a base under siege drama. Even of the villain of the piece may or may not have been seen before. If King wasn’t so good at the formula, it would be so much easier to scorn all but the original attempts at his oeuvre. Storm Of The Century may offer little in the way of new storytelling, but its trademark lengthy build-up of menace and character development work once more to good effect, tense atmosphere all-pervasive, and its villain compelling and well-acted.

Even when the human participants of Stephen King’s novels are rather idealised caricatures of humanity, the author always pulls them away from the edge of schmaltz with his strongly Christian morality of mankind’s frailty. Virtually every adult of Little Tall Island has ‘sinned’, be they adulterers, thieves, drug runners or closet homosexuals lashing out American Beauty -style. Regardless of one’s own perspective on the vices presented, Storm Of The Century’s morals are very black and white, and they need to be in order for the villain to function in the story, judging them from on high for their faults. Some reviewers I have come across online have found the townspeople therefore so unlikeable and hypocritical in their pretense at professing to be good, Christian parishioners, that they have found themselves in many ways siding with the story’s antagonist. Others still have been so disgusted that they refuse to believe such people actually exist. As King demonstrates, it is only extreme duress that people will reveal their inner demons, and the most vehement denial may come from the very people he condemns for their doublethink. How well do we really know anyone? we are compelled to ask.

The strong Christian morals of the story dictate that children are angels and adults have succumbed to temptation. The heavyhanded eulogising is central to the plot.

This, ultimately, is perhaps the true horror of Andre Linoge. Fairly explicit lines of dialogue imply his Biblical origins, a background he shares closely with the chief antagonist of The Stand and the Dark Tower series. Until we find out precisely what he wants of his victims, the tale seems to be the book of Revelation in miniature, except that salvation may lie in wait for no-one once Little Tall’s list of crimes has been read. Yet it is not Linoge’s demonic origins that terrify us, but his ability to force us to drop the masks we hide behind in our attempt at civilization. His disgust at the inhabitants is not so much their hidden criminality, but their pious masquerade atop foundations of insecurity. King’s religious beliefs prevent his characters from adopting the excuse that they are merely behaving as all animals do – the veneer of civilization atop barbarism cannot be equivalent to the skein of sentience thinly stretched across millions of years of instinct. These are a people ‘born in sin’ willfully straying from the path laid out for them by God, and their stubborn denial of their nature dooms them from the outset – able to keep secrets, they are easy fodder for the demon who knows they will tell no-one of his presence. Unsurprisingly therefore, those same viewpoints depict children as beings of perfection – until of course they hit puberty, where sexuality instantly makes them sinners, of which the drama has several such examples. The cynical viewer may put off by the oversimplistic Christian moralising of the piece (not to mention the rather sickening idolisation of the young along the lines proscribed), but will at the same time be compelled by the uncompromising treatment of humanity that unfolds. It may be King’s most Christian-themed tale, but that brutal reckoning of human nature is a common element of his stories that reels his fans in so successfully.

“The cynical viewer may put off by the oversimplistic Christian moralising of the piece (not to mention the rather sickening idolisation of the young along the lines proscribed), but will at the same time be compelled by the uncompromising treatment of humanity that unfolds.”

All of which could fail miserably if not realised well on screen, however, the acting and production values are generally up to the challenge. Filling the boots of self-righteous town hero is actor Tim Daly, known to many as the voice of fellow moral crusader Superman, and possessing just the right looks and bearing to play alpha male and Little Tall Island’s chief of police, Michael Anderson. Daly effortlessly convinces as a well-liked leader figure, more religious than the town priest and more capable than the self-serving town manager Robbie Beals, excellently portrayed by Jeffrey de Munn, who again just looks the part. As does Debra Farentino as Anderson’s wife Molly, who in every way must be alpha in female form, and Farentino delivers. The assembled cast, many wielding that distinctive Maine accent one would expect (and I now know how to pronounce ‘Ayuh’) are by and large as I would have imagined them to be, and every bit as proud and defiant of their superficial outer values as they should be.

Colm Feore, meanwhile, does a fantastic job as Andre Linoge, the dark stranger making impossible demands of the town. Feore gives a carefully balanced performance, neither over-the-top as the part so easily descent into nor too understated to be sufficiently menacing. His Linoge is long-lived, world-weary, and tired of humanity’s self-deception. Yet for all this, he is intelligent and capable of compassion. Murder is seen as a necessity to prove a point, but not something to be dispensed randomly. Feore manages to depict this complexity well, perhaps descending into pantomime only when forced to display Linoge’s animalistic nature.

The character’s supernatural nature is where much of Storm Of The Century’s CGI comes into play, as well as helping render the storm of the title. It’s pretty good for a television miniseries made in 1999, as is the enormous island set used throughout. That we’re on a soundstage is fairly obvious in places, but understandably necessary in order to realise the many practical effects needed to create a town beaten by the weather. This is enhanced further by judicious use of additional shooting in Canada and fairly seamlessly interwoven.

I was in fact only dimly aware that Storm Of The Century had been a miniseries, and watched its entire 4 hours of runtime in one sitting. To me, it had been a surprise find on VCD in Hong Kong the following year and having experienced IT, The Langoliers and King’s 1997 adaptation of The Shining in much the same fashion, Storm Of The Century simply seemed another epic in the same vein. However, this is to undersell the well-paced script, acting and Craig R. Baxley’s direction which are ultimately the reasons why such a long commitment was not overlong. For all its flaws and painful moralising, Storm Of The Century is another successful squeeze of the lemon by a writer in his element. It offers nothing new, but is very good at rehashing the old, and something most King fans will find plenty within to enjoy. And is Andre Linoge Randall Flagg? Let’s not go there.

******

Next Time

As the icy winds of winter depart the northern hemisphere for the south, we’ll be travelling with them all the way down to the South Pole for a special 4-part miniseries on Antarctica. I felt that one week in the massive continent wouldn’t do it justice. The selected films will cover both fiction and non-fiction, through which Antarctica will be viewed as both a place of wonder and exploration, and also a dangerous white wasteland and time-serving outpost for the ordinary worker.

First up, we travel back to a time when the South Pole captured the imagination of the world: On November 1939, two vessels carrying 125 crewmen between them departed Boston for the Antarctic. Travelling with them was a young man about to make filmic history. The first chapter of Antarctic Film Month next, when World On Film returns.

Close To The Edge

This week: isolation, abuse, and vengeance in Yang Chul-soo’s provocative horror-thriller, Bedevilled. World On Film is currently on break from its main series of film reviews, but having watched this recently, I couldn’t resist throwing in my two cents’ worth. Fans of Korean cinema can also read my brief account of my time at the 2010 Pusan Film Festival.

Bedevilled

(2010) Written by Choi Kwang-young Directed by Yang Chul-soo

“There are kind people?”

Turning point: a woman tortured by an uncaring world reaches the end of her patience in 'Bedevilled'.

When Hae-won, a highly-strung and unsympathetic young woman, is forced to take sick leave from her high-pressure job as a clerk in a busy Seoul bank, she decides to recuperate on Moo-do, the remote southern island of her birth. There, she is reunited with childhood friend Bok-nam, who unlike Hae-won, never left the island in search of greater fortunes, and lives with a violent wife-beating husband, a brother-in-law who routinely rapes her, and village elders who despise her for being a woman. Matters reach breaking point when her husband turns his lecherous attentions to their young daughter, and Bok-nam can finally endure her abuse no longer. However, her friend even now may not be on her side.

Script-writer Choi Kwang-young quickly earned a name for himself in 2010 with the release of two crime-thrillers, the first being Secret Reunion, which I reviewed last year. While it fell far more into typical odd-couple comedy territory, Secret Reunion did nonetheless contain some quite brutal murder scenes, suggesting that Choi might well have intended his tale of a North Korean assassin infiltrating the South to be far darker. Bedevilled, therefore, feels like the next logical step.

The film takes a character trapped in a loveless marriage and a cycle of endless abuse and asks what would happen if she were pushed over the brink.

Meanwhile actress Seo Yeong-hie had by this time already proved herself a veteran of grim, blood-splattered thrillers, having played one of the lead roles in The Chaser, in which police struggle to catch a twisted serial killer who preys on young women in a downtown suburb of Seoul. There, Seo gives a memorable performance as one of his prey, and in going on to play the tortured character of Bok-nam in Bedevilled, has seemingly become the go-to performer when casting abuse victims. Hardly surprising, since in Choi’s uncompromising melodrama, the female protagonist is put through the wringer akin to those in Pascal Laugier’s squirmfest, Martyrs, with Seo providing a painfully incredible, and indeed real, performance.

Some viewers may have trouble agreeing with this verisimilitude, given that the island is populated by a series of characters so horribly sadistic and sociopathic that it may be hard to accept the idea of anyone in real life being so horrible. However, Choi draws his characters from the cultural wellspring of what is still one of the most patriarchal societies in the world, where historically man was the undisputed ruler of his domain and woman was his property, there only to tend to his needs. Since it was the traditional male role to look after the parents in their dotage, men were valued far higher than women, who would inevitably marry into another family, and daughters-in-law were therefore little better than indentured servants. This attitude is compounded still further in the rural setting we see here, where only men are deemed capable of the endless physical labour required for survival. Korea’s gender imbalance is testament to the enduring nature of the long-held Confucian belief, and only beginning to dissipate in more modern times. Bedevilled’s cast sits at the extreme end of the scale, which Choi has taken to its logical conclusion: a remote island populated by characters uneducated, far from modern social attitudes and driven to antisocial behaviour due to their isolation, and the almost Wrong Turn-like devolution is the result. However, it is not a cheap shot commentary on the isolated community of hillbillies, but the effect they have on their unwitting servant that sits at the heart of the film.

Young daughter Yeon-hee, already corrupted by her lecherous father and doomed to follow the path of her mother unless both escape their island prison.

Bedevilled is something of a catharsis for every woman who has ever suffered the indignities of male-dominated social imprisonment. That same society teaches such women that suffering is part of existence, and something they must bear with fortitude, no matter how great or for how long it may be inflicted upon them. Kim Bok-nam however, is taken over the edge, and when the moment comes, Bedevilled rapidly begins to earn its slasher-horror stripes. On the one hand, it plays like a very typical Korean melodrama, with abuse and indignity piled upon the tortured lead until you begin to wonder how anyone could possibly endure any more. This is contrasted with the character of Hae-won, played by Ji Seong-won. She too is a victim of a male-dominated world, but is both too afraid to confront it and lashes out the wrong people because of it. Yet her abuse is inflicted in stages rather than as dramatically as Bok-nam’s, pushing her into self-absorbed narcissism rather than sympathetic compassion, depriving Bok-nam of her one remaining lifeline to sanity. This is of course is necessary if Bok-nam’s eventual descent into madness and quest for swift revenge is to be believable, and not simply the cheap contrivance of B-grade horror. Precisely because it is done properly is why Bedevilled is so powerful, and in a cast of such thoroughly unlikable characters (again, necessary to justify what is to come), it is the murderer with whom we ultimately have the most sympathy.

“Bedevilled is something of a catharsis for every woman who has ever suffered the indignities of male-dominated social imprisonment.”

For all this, the script is unburdened by heavy-handed morality. There is a complete lack of “This behaviour is wrong because…” or “That’s what you get for being a rapist!”-type dialogue throughout. Bok-nam, who had known no-one else but the unsympathetic islands her whole life, has no basis for comparison for most of the film, thus her judgement is based purely on her experiences, allowing for an organic rather than didactic tale despite its pro-feminist overtones. It would be hard to imagine the inevitable Hollywood remake treating its viewers in such an intelligent fashion.

Unsympathetic family and friends find themselves the target of a vengeance they are too selfish to understand.

Shot on location on Geum-o Island in Korea’s south, Bedevilled has the perfect visuals to create its prison-like setting, contrasting them with Seoul’s concrete wilderness, which is not necessarily seen in a much better light, where misogyny is no less rife. Full credit to cinematographer Kim Gi-tae for simultaneously bringing out the stark contrast between these two locales yet showing their dark similarities.

The film does suffer from certain issues, firstly a tremendous jump in the action at the climax, presumably done for reasons of time, but standing out a mile. It raises questions about how certain characters manage to end up from one location to another given their predicament, and is something that director Yang Chul-soo cannot have failed to miss. Also, while the gore scenes are for the most part handled as realistically as one could imagine them being, Bedevilled does suffer a little from Michael Myers/Jason Voorhees syndrome, where antagonists cannot possibly have managed to survive the death blows inflicted upon them so unharmed, forcing the audience to put the superhuman endurance down to masses of adrenaline caused by madness. Still, noticeable though they are, the discrepancies do not undermine the story’s principal aims, and one way or another, Bedevilled burns its mark into the psyche – or should that be ‘slashes’?

Full marks finally for the subtitles on my copy, which being the official release, should be the same for you as well. You know a film is being translated well when the subtitler works hard to capture dialect and slang in another language. In Moo-do’s grotesque denizens, it manages to heighten their inhumanity, while in Bok-nam, it brings out the simple, country girl who yearns for both affection and to see Seoul, which through Hae-won, she has equated with the entire world beyond.

Ironically, I have yet to meet any Koreans who have seen Bedevilled, although that’s clearly just the people around me, and they all knew it by reputation. Its dark, unsubtle character study and melodramatic brutality, not to mention blood-splattering second act will not endear it to many, but when viewed in the right context, which I have hopefully established for the reader above, it functions as an extremely powerful film and comes highly recommended.

In case you’re wondering, the original Korean title, which rather gives everything away roughly translates to ‘The Circumstances Surrounding Kim Bok-nam’s Homicidal Episode’. Then again, subtlety is not the point of the exercise here.

*****

Next Time

And now, for something completely different. Several months ago, I had fun writing about two of my favourite soundtracks to films I hadn’t actually seen before. While a good score should arguably be inconspicuous, it takes on a whole new meaning when heard in isolation. On this occasion, I look at two soundtracks to films that I would go on to see and attempt to put what I at least can hear into words – a possibly foolhardy and ill-advised effort that may make counting sheep an adrenaline-filled rush by comparison. The two scores thus afflicted are Neil Diamond’s Jonathan Livingstone Seagull and Victoria Kelly’s Under The Mountain next, when World On Film returns.

Back On The Bottom Line

This week, romance in Benin as World On Film explores the straight-to-video Nollywood ‘classic’, Abeni, which until now, I had happily forgotten all about. We also discover the signature work of amateur English film-makers Wild Herb, who, despite being very visibly strapped for cash, manage to achieve what the BBC seemed utterly incapable of last December: a literary adaptation that actually used the book as its reference point.

Before we dive in, I’d just like to quickly mention that I have learned slightly more about WordPress in the last week and have added a search function to the blog – well, several actually, until I can figure out which are more useful. Scroll to the bottom of the main page to see how you can more easily access past entries, and I hope those widgets make life easier.

And now, brace yourselves for the entirely unnecessary existence of:

Abeni

(2006) Written by Yinka Ogun & François Okioh; Directed by Tunde Kelani