I Never Thought I’d Live To Be A Hundred

This week, World On Film visits the African state of Congo. Ah, but which Congo? This was the difficulty I faced when searching for visual material recently. Even the Internet Movie DataBase incorrectly lists many films as being made in ‘Congo’ when they in fact mean the Democratic Republic of Congo. The much larger DRC after all is Africa’s second-largest country and like North Korea, tends to be the greater source of conflict and instability than its near neighbour. But what of the Republic of Congo, the much smaller ex-French colony lying just to the West? It shares a similar history: stripped of its mineral wealth by foreign powers for over a century, racked by waves of civil war and home-grown dictatorships since achieving its independence, and leaving a near-destitute population shell-shocked by the worst depravities of man and facing a bleak future due to lack of infrastructure. For both Congo republics, the story is a shared one, the plights of their people struck by the same destruction.

In the end, however, I did come across one very positive short film showing the efforts made by at least one small organization to give today’s youth in the Republic of the Congo reasons to live for tomorrow.

The Flux Mothers

(2008) Produced by Jacob Foko

“I would like to have a life like every other girl. I want to be intelligent, read, write. I want to have a better life like them. That’s all.”

Holistic approach: In ‘The Flux Mothers’, we see a program designed not only to give Congolese women much-needed job training, but a well-rounded education for a sustainable future.

The DRC is typically referred to as the ‘rape capital of the world’, yet many young women in the Republic of the Congo have also had to face firsthand this most long-term destructive example of social breakdown. Impregnated as young as 12, they now find themselves saddled with children they do not necessarily want nor can afford to provide for. However, rape is not always the catalyst: in an environment without social welfare, affordable education or job prospects, many women will look to men as a means of survival, only to find themselves dumped when impregnated. Destitution and complete lack of self-worth are compounded in rape victims by mental trauma, especially in a strongly patriarchal culture.

“For both Congo republics, the story is a shared one, the plights of their people struck by the same destruction.”

The Flux Mothers introduces us to a Dr. Ann Collet Tafaro, the driving force behind humanitarian aid organization, Urgences d’Afrique, a program designed to train young Congolese woman such as described above in the art of welding, thus giving them a practical skill in high demand across the region. However, practical skills are only part of the equation, since women who register for the program are also given free language and literacy classes, health-care training, and psychological counselling. Tafaro ultimately understands that in Congo’s war-ravaged environment, any attempt at humanitarian aid must go far further than simple job-training. It must also heal the mind and rebuild an individual’s identity from the ground up.

The film also shows that like all humanitarian aid efforts, there are massive holes in the program due to lack of funding – no safety equipment, poor medical facilities, and a paucity of raw materials that any average shop class would stock. Just as the Congolese must make do with the little they have, so Tafaro and her students must do likewise.

Above all, I found The Flux Mothers to be very inspiring, and given that it was made four years prior to this post, it would be interesting to see how much the program has progressed. In the meantime, the film-maker himself has uploaded the film to Vimeo, which means I can present it below. It was produced through an organization called Global Humanitarian Photojournalists, with the aim of attracting donations for Tafaro’s program.

<p><a href=”http://vimeo.com/22004375″>The Flux Mothers</a> from <a href=”http://vimeo.com/jacobfoko”>Jacob Foko</a> on <a href=”http://vimeo.com”>Vimeo</a>.</p>f*****

The Opaqueness of Sustainability

Sometimes, getting visual material to watch for a particular country can turn up some truly bizarre results.

Several years ago, I came to hear a few tracks off a new album I mistakenly believed to be the work of the late Donna Summer. It was an obvious mistake: after all, the album was credited to a ‘Donna Summer’ and given the title ‘This Needs To Be Your Style’, which seemed to fit – was not Donna Summer a woman of great style? Then there was the ‘music’ on the album itself, a motley assemblage of aural cacophony that even Bjork would only think fit to record after six months of heavy acid usage, occasionally interspersed with twisted samples of familiar tracks by the disco queen herself.

What I did not know was that ‘This Needs To Be Your Style’ was in fact the work of ‘Donna Summer’, aka British electronic and breakcore obsessive, Jason Forrester, who adopted Summer’s name for stage purposes. I mean, it’s obviously really, isn’t it? It didn’t help. Knowing the real intent of the album did not somehow magically reassemble the mad mix into something coherent – which for all I know is what breakcore exists in the first place.

Many years later and not long after the real Donna Summer released what would be her latest – and last – album, I found myself given the dubious pleasure of editing bid proposals by various organizations hoping to secure international conferences. It could be an interesting job in theory, but for the fact that I quickly discovered that none of the bidding hopefuls knew the first thing about how to sell their host city as the site of a potential global congress. Thus would the Power Point presentations and PDFs be a soul-destroying kitchen-sink collection of random facts interesting to no-one and of dubious connection to the main thrust of the proposal’s argument, which itself was only optionally present. Perhaps the authors felt that to assault their audience with a barrage of facts and figures would beat them into stupefied submission, if not baffled silence, causing them to cave in completely.

“Sometimes, getting visual material to watch for a particular country can turn up some truly bizarre results.”

So, then, we see that context is everything, but your ignorance of that context does not always mean your hosts know what they’re talking about. Which brings me to this Congo-focussed oddity.

SOPI Architects, an architecture/urban planning firm based in the UK and Cote D’Ivoire, once put together a proposal for achieving sustainable development in Brazzaville and beyond. Following what has to be the longest company ident in history, we see a curious mish-mash of a film that centers around showing us a long text-based feasibility study that seems ultimately to conclude that what the Republic of the Congo needs more than anything are more attractive buildings. Well, you would expect an architecture firm to say that. The problem, however, is that the other 98% of the video (8% of which worships the ident) does not really build up an argument in this direction, preferring instead to take the scattershot approach of throwing in facts and figures about the country’s development problems across the board.

At least I assume that’s the case, given that the text is too small to read, and not on screen long enough to read in any case. It appears for all the world as if someone has filmed the pages of a book, more to show you what each page looks like rather than an effort to help you read it. There is also the apparent assertion that you are fluent in both English and French, given the randomly-inserted talking head video clips predominantly in French despite the English text, and not subtitled. The footage is also a strange collection, at one point a long self-congratulatory sermon from no less than the nation’s president, Denis Sassou Ngouesso on forest preservation to clips of flood victims complaining – and quite rightly – about the ease with which their villages are frequently underwater.

Like ‘This Needs To Be Your Style’, it’s all over the place. One could argue that I may have failed to grasp the finer subtleties of the argument – maintaining forests + shoring up river banks = build more duplex apartments – but I remain skeptical on this point. At any rate, if you would like to make sense of the presentation, you can watch it below.

*****

Next Time

“The island’s seemingly impenetrable mass of opaque green palm trees and tooth-jagged mountain ranges easily suggest the untamed exotic Javan wilderness far from Batavia’s comparative civility of more than half a century ago”

World On Film visits the Cook Islands in the South Pacific, looking at examples of their use in storytelling – typically as a stand-in location for somewhere else. You can see a trailer for one of these examples below. We also take a good look at the archipelago as it truly is, and I can already say it’s convinced me to go there someday. That’s next time.

The Balance

This week, World On Film travels to the small island archipelago of Comoros and finds out what happens to those left behind – and those who should never have been there in the first place. What does all that mean? Read on…

The Ylang Ylang Residence

(2008) Written by Hachimiya Ahimada & Katia Madeule Directed by Hachimiya Ahimada

“It’s happening to the neighboring houses too. The owners abandoned them. They forgot this is their land.”

“It seems they’ve forgotten us too.”

Comoros’s first official film, ‘The Ylang Ylang Residence’, explores the importance of community after mass emigration takes its toll.

Many years ago, I remember reading former New Zealand Minister for Communications David Cunliffe complaining about the national “brain drain”, an apparently rampant phenomenon in the previous decade wherein many of his skilled and talented fellow countrymen were relocating overseas in search of better job opportunities and leaving a major social void in their homeland. Consequently, the ‘returnees’ who’d made good and wanted to bolster those opportunities back in New Zealand, like a certain Peter Jackson, were all the more applauded.

Cunliffe was of course speaking of a phenomenon as old as civilisation itself, and indeed anyone trying to make it in a film industry outside of Hollywood or its Indian and Nigerian counterparts knows all too well just how dry is the creek bed of employment. He, however, was also speaking of the IT industry and of industry in general. How then does abandoning one’s homeland for pastures greener affect those in impoverished nations?

In Hachimiya Ahimada’s short film, The Ylang Ylang Residence (aka La Residence Ylang Ylang), the tiny East African archipelago nation has lost many of its people to France and beyond seeking escape from a home with no future. In the principal island of Greater Comoros, dour young resident Djibril continues to maintain the stately former home of his brother, now gone for the past twenty years and unlikely ever to return. When an electrical fire burns his own modest house to the ground, Djibril and his wife are forced to rely on others for help. One neighbour even suggests he move into the abandoned family home, but somehow, it just doesn’t feel right…

“How…does abandoning one’s homeland for pastures greener affect those in impoverished nations?”

Although seemingly emotionally-distant, Comorians are seen to be highly group-oriented, an interesting dichotomy for this most culturally-cosmopolitan people.

The Ylang Ylang Residence is Comoros’s first film, and shot on 35mm, is in no way any the lesser for its short running time of 20 minutes. The island archipelago has had a very chequered history, still affected by occasional civil war today. It also has a truly cosmopolitan history, due to its proximity to Africa, the Middle East, and Austronesia, the cultures from which have all left their mark across the centuries. In the film, this is evidenced by the fact that those who have returned have elevated their social status by previously living and working in France, the predominance of Islamic culture, and the language of the film being Arabic – just one of the languages used on the islands.

Perhaps this explains the profound level of formality, politeness, and above all emotionless reserve displayed by the characters of the story. Every line is stilted, every face a blank tableau of inscrutability, which seems to suggest the people of Greater Comoros are only half-alive and going through the motions of existence, with all inner hopes and dreams stifled by a lifeless economy, few prospects, and an authoritarian religion.

Yet the great irony of all this is that The Ylang Ylang Residence is also a film about knowing who your friends are in times of hardship. For Djibril and his wife, when family has deserted them, salvation comes in the kindness of strangers, or more accurately, friends and neighbours. It is the kind of communal altruism we typically romanticise as being the lifeblood of rural areas, yet in reality is by no means guaranteed to occur. If it shows anything about Comoros, it’s that twenty minutes is nowhere near enough time to truly understand this complex, multi-layered culture. Ahimada clearly agrees, and is doing something about it.

“In 2008, I directed my first fiction short cut Ylang Ylang Residence in Great Comoro island. Actually, I am working on my documentary project ‘Ashes of Dreams’ which is located in the whole Comoros Archipelago. I am editing it now.” (Source: MUBI.com)

That source, by the way, is the only place I know of where you can see The Ylang Ylang Residence. For 99 US cents, it’s well worth it.

*****

I also watched…

On the 23rd of November 1996, Ethiopian Airlines Flight 961 was hijacked on its way to Nairobi by three Ethiopians planning to seek asylum in Australia and forced to land in the waters off Comoros when the fuel ran out. 125 of the 175 members of the passengers and crew died in the incident, including the hijackers. It is also noteworthy for the fact that it is to date the only time an aircraft of its size – in this case a Boeing 767 – made a true water landing and with survivors aboard. The actual footage of the landing can be seen below:

It’s perhaps unsurprising that someone would eventually attempt to dramatise the fate of Flight 961, and this indeed was the case with the Ethiopian movie, simply titled Comoros. It is more disheartening however, that the Ethiopian film industry concluded that what was really needed to mark the occasion was a poorly-constructed melodrama that had actually very little to do with the real-world events which spawned it. The end result proved to be about as intelligent as opening up a white goods store in Amish country and every bit as misguided.

The ‘story’, which convention dictates we’ll have to call it, centres around the incredible sinewave-like existence of Edie, a young Ethiopian flight attendant, who proves to be as dangerous to hang around as Jessica Fletcher. Striving to make her way in life following the tragic deaths of her parents, Edie meets Mike, a young business executive, they fall passionately in love and soon produce a young son, much to the immense delight of Mike’s mother-in-law. The child then proceeds to almost drown in a river before finally being killed off for good in the Flight 961 disaster. Mike’s mother, who from the outset has made no secret of the fact that a daughter-in-law’s only usefulness is to produce a son, promptly disowns Edie while belittling and insulting her very existence in an unnecessary attempt to prove how completely unpleasant the old woman truly is. As a result, the beleaguered young wife, further motivated by the profound ennui exhibited by her husband, resolves to give her ungrateful in-laws another child. Except that the doctors have made it absolutely clear that she risks death by any further pregnancies and would be stupid even to try. Add several more tragedies and you have Comoros, ninety minutes of shirtsleeve emotional indulgence that makes Days Of Our Lives look like Last Of The Summer Wine.

“The end result proved to be about as intelligent as opening up a white goods store in Amish country and every bit as misguided.”

However, a dire plot was not enough of a crime for the forces behind this histrionic farce. Acting with more ham than an Elvis breakfast was subtly combined with ludicrous production choices, the worst offender of which was the presence of long sequences involving dialogue between characters that we can’t actually hear. There’s nothing Ethiopian about it. Azerbaijani karate krapfest Seytanin Talesi reveled in forcing the audience to watch pointlessly mute conversations just to show the act of people talking in case anyone out there didn’t know what it looked like. Comoros however ups the incompetence ante by overlaying a constant stream of banal narration from the lead character herself that to a seven-year-old might seem highly profound and to anyone no longer in short pants, commits the hideous crime of telling rather than showing drama.

“Mike’s secretary told me that Mike had all but stopped working since the tragedy. Although I understand why Mike is grieving, finding a way to bring him out of his misery is proving difficult.” – ‘Crucial’ narration accompanying a sequence where the audience can clearly see Mike not working, and Edie unable to reach him.

Menacing matriarch: unpleasant and uncompromising parents-in-law are a popular staple of African melodrama. And Korean melodrama, for that matter.

Comoros also shares another of Seytanin Talesi’s dubious production choices, that of employing only about three pieces of generic mood music, which are then re-used endlessly throughout the film, ill-fitting the mood of every single dramatic sequence they accompany. Clearly convinced he is onto a winner with this approach, the director even commits what can only be described as an act of true genius by often piping in the music before the mood of a story element is visually-apparent, thus saving the viewer the agony of having to figure out how they should interpret the drama themselves.

And of course we have the African social stereotypes: the young independent woman who quickly becomes subservient once her true goals of marriage and procreation are realised; the moderate, progressive son who must kowtow to the whims of his ultraconservative parents; the utterly ineffectual but well-meaning sibling; and of course, the reprehensible parents of the son who demand worship yet spit venom upon anyone not living up to their narrow standards of existence. The problem is not the presence of these archetypes. They clearly exist and demonstrate the generation gap in today’s Africa (with the caveat that ‘Africa’ is of course a huge assemblage of differing cultures and peoples, but Nollywood-style cinema appears not to have noticed this), thus there is an audience who keenly relates to their behaviour. The problem occurs when the characters are presented in this ridiculously two-dimensional pantomime fashion, resulting in it being impossible to take any of them any more seriously than a high school debating club talking about the evils of the corporate world. Last year, I reviewed a Nollywood film exhibiting much the same cheap character.

In a way, I’m glad I was unable to find any production information on Comoros. Watching it was more than enough punishment – as it will be for anyone else who dares to watch it – like you, if you click on the video below.

*****

Next Time

We find out how the young women of the Republic of the Congo are being given a new future and also learn why coherence is so important when making any kind of visual presentation. That’s next time, on World On Film.

Going Nowhere

High up in the Colombian Andes, a squad of soldiers manning a remote mountain bunker mysteriously all go missing. Believing their disappearance to be the work of the enemy guerrilla, base command sends another squad to investigate. However, the new arrivals soon find themselves unwittingly re-enacting the events leading up to their predecessor’s fate and it may not be the work of enemy agents.

The Squad

(2011) Written by Tania Cardenas and Jaime Osorio Marquez Directed by Jaime Osorio Marquez

(You’ll find a trailer at the bottom of last week’s post)

“Haven’t you realized it yet? There’s nobody out there! The only murderers are us, goddammit!”

Fear and hatred keep the wheel of conflict turning in Jaime Osorio Marquez’s claustrophobic horror-thriller, ‘The Squad’.

The above quote may seem to give away the film’s twist, but The Squad, sitting somewhere between horror and claustrophobic thriller, is a dark tale that will keep you guessing until the end. Taken as horror, it’s a story that benefits from director Jaime Osorio Marquez’s solid understanding that invoking the paranormal effectively benefits from the ‘less is more’ approach. This is not a man interested in cheap thrills. In fact, some viewers will question whether or not there really is a paranormal element to the film, given that it flirts with, but never conclusively states, an otherworldly force behind the drama. The most obvious example, and I will try to avoid spoilers, is the soldiers’ discovery of an old woman seemingly kept prisoner by their missing comrades. Speculation turns to fear when she is accused first of being a guerrilla spy, then an unfortunate local caught up in the country’s perpetual civil war, and then a witch – in any event the source of all the misery that befalls anyone cursed with entering the bunker. Marquez walks a fine line with all three possibilities, and gives just enough circumstantial evidence to allow the viewer to conclude that any one of them might be true.

However, since The Squad is so Spartan with its horror elements, it is predominantly a thriller about claustrophobia and fear in general. The war has completely polarised both sides of the conflict, and so the only dimensions of character among the soldiers we meet range between the aggressive, bullying nationalists and the moderates forced into a military environment they have no taste for, yet they too have no sympathy for the other side. It’s probably the most important thing to understand about the citizens of any country where national service is mandatory.

The film explores the way in which perpetual civil war has enslaved the mind and terrorised the soul in modern-day Columbia.

Add to this a deep sense of battle-weariness that the characters seem almost to breathe out from the very first scene. Although the narrative is entirely confined to the isolated Colombian outpost, lines of dialogue make it clear that this is simply the latest in a long line of engagements with the enemy. In peacetime, we often have trouble wondering how certain people are able to commit certain acts, and in The Squad, the elastic has already been stretched a good way for everyone involved. This, we are being told, is what it means to live amidst civil war.

Then the story actually begins and, after a quietly tense sequence in which the characters survey their surroundings, the screws start to be tightened even further. In many ways, The Squad is a base-under-siege film, both figuratively and literally. Visually, Marquez could not have chosen a more perfect location: it really is a bunker high up on a mountain somewhere, where the fog is so frequent that venturing in any direction will make you hopelessly lost if you’re lucky. The weather itself is a mental and physical barrier. All of which only helps make the ‘siege’ very much the cabin fever variety, taken to new heights by human weakness and paranoia. Already convinced they are under attack by guerrilla forces that always seem to be one step ahead of them, the unraveling of self-control for each beleaguered soldier seems only a matter of time. Yet as indicated earlier, there may be other forces at work.

“In peacetime, we often have trouble wondering how certain people are able to commit certain acts, and in The Squad, the elastic has already been stretched a good way for everyone involved.”

The sudden appearance of a woman who may or may not be in league with forces beyond human understanding throws a genre curve ball in what is predominantly a more down-to-earth and visceral base-under-siege film.

I couldn’t help but be strongly reminded of the in-many-ways-similar Korean horror-thriller Antarctic Journal, where a group of initially optimistic team of scientists attempt to be the first Koreans to reach the South Pole. There, writer/director Yim Pil-Sung similarly tries to offer both mundane and supernatural reasons for the group’s ultimate descent into madness and murder, so much so that he almost makes two different films running concurrently, and the whole doesn’t quite come together. Marquez is clearly the more adept at weaving the seemingly real with the seemingly unreal – perhaps because his main commentary is upon the prolonged effects of war on the psyche, especially when cornered. And yet in many ways, I find Antarctic Journal the more enjoyable film for all its faults.

Perhaps The Squad is too claustrophobic. Its protagonists, seemingly doomed to begin with, make the transition from ‘bad’ to ‘worse’ rather than Antarctic Journal’s ‘good’ to ‘bad’. We are thrown into the tension almost immediately, and when characters aren’t descending into madness, they are sniping at each other or making intense declarations of family loyalty. The true protagonists of the story are helpless from the outset, dominated by their unstable, aggressive and wholly unpleasant colleagues. Add to this an ongoing barrage of tight close-ups, washed-out colour and a very confined set, and there really isn’t room to breathe in The Squad. On paper, the almost Blair Witch-like approach should work well, but you can have too much of a good thing.

Excellent and atmospheric location choices help overcome some of the film’s lack of thematic coherence.

And perhaps the imbalance of the supernatural and the more down-to-earth brutality of the situation is another factor. If the film is allegory for the horrors of war through the use of supernatural elements – as John Carpenter’s The Thing is allegory for Antarctica-as-blue-collar-dystopia via sci-fi elements – then it doesn’t go far enough to work as allegory. Or to put it another way, while I applaud Marquez’s carefully-judged use of the supernatural (if, again, that’s what it is – and it’s up to the viewer to decide this) for the purposes of intelligently-made horror, there’s too little of it to work as a symbol of real-world psychological fear. Equally, since The Squad is therefore mostly a real-world study of human madness, that weighty discourse is derailed somewhat by occasionally saying ‘Hey, maybe these guys are being manipulated by forces beyond their understanding.’ This is where Antarctic Journal also ultimately fails: film-makers not deciding clearly enough as to what their story is ultimately about.

Which is a shame, as there are certainly a lot of interesting ideas in The Squad and a location setting that was absolutely made for horror. Then again, if true horror is human behaviour, then those Colombian mountains have likely already told that story many times over the years. While the film lacks clarity in some areas, not even the cold blanket of the fog can enshroud the utter senselessness of a never-ending conflict that exists now only to consume man until nothing but his fear-stained face, frozen in death, remains. If the film-maker somehow lost his way slightly in getting his story across, there is a certain irony in the fact that his characters – and the real-world analogues upon which they are based – are so deep within their society’s conflict that they are fated only to disappear without trace, like the lost people of whom they came in search.

*****

Next Time

We travel to the remote island archipelago of Comoros and discover how the locals cope with the country’s massive brain-drain in its very first film, The Ylang Ylang Residence. Plus: how to turn a real-life tragedy into a cheap melodrama. Air disasters and asinine production choices in the Ethiopian farce Comoros – next time on World On Film.

An Ocean Full Of Faces

A bright full moon pushes through the blue haze of the daytime sky over The Settlement. The warm November breezes herald the approach of another hot sub-tropical summer, and excuses are made all through the town to eschew haste for leisurely engagement to the business of survival. Yet some of the island’s inhabitants have no time for this relaxed philosophy. From all directions They come, caring nothing for demarcation lines between man and motor. On every pavement, in every street, across every veranda, and through every backyard, they cover the town in a scuttling sea of red. One hundred million bundles of busy legs exchanging their sunless burrows for the shining, sandy shores of the beaches beyond the palm trees and the bubbling blue waters of the ocean beyond. Not for them the pleasures of this sinewave surfer’s paradise, but the unquestioning duty, the unwavering need to spawn the future. Just as they did last year, just as they will next year and for all the years to follow. They are the red crabs of Christmas Island.

“The whole place is overrun with curious red crabs as much as 18S in. across. They are excellent tree climbers, and once a year there is a regular migration of these crustaceans who travel in bodies like ants, taking 15 days on the journey, and returning inland after hatching their eggs.” – The Examiner – Launceston, Tasmania, 14 May, 1901, expedition of Sir John Murray.

In 2002, the Australian documentary series Island Life explored the far-reaching impact of this remarkable species, endemic only to Christmas and Cocos Islands (both Australian territories), and the increasing threats it faces by humanity and its influence. Two in particular currently affect the fate of the red crabs. Caring little for the presence of Christmas Island’s self-appointed owners – predominantly European and Chinese – crabs unwittingly braving the tarmac often fall victim to the heavy tyres of mining trucks filled with the precious phosphate that gives the locals their main economy. Fortunately, miners are reasonable people and awareness programs have made good progress in teaching them of the importance of preserving the rare local fauna.

“On every pavement, in every street, across every veranda, and through every backyard, they cover the town in a scuttling sea of red.”

Far less reasonable is the second, and far more deadly, threat the red crabs face. Accidentally introduced into the local ecology from Africa a century ago, the yellow crazy ant today decimates all that stands in its path. “Listed among the 100 most devastating invaders of the world,” says Wikipedia (the entry has an extensive references section), “it has invaded ecosystems from Hawaii to Seychelles, and formed supercolonies on Christmas Island in the Indian Ocean.” Formic acid, their chief method of attack, blinds their prey, eroding areas of its body or simply causing it to starve to death. Large and unwieldy in comparison to its tiny and determined predator, the red crab has little chance of escape. Equally disadvantaged are its distant relative, the coconut (robber) crab, and other mammals and plant life sharing the surrounding environment.

The outlook was fairly grim in 2002, with fully a third of the total red crab population wiped out by the unstoppable invaders. That same year however saw major countermeasures launched by local wildlife officers. Ground and aerial baiting efforts using fipronil, a fish protein-based poison lethal to insects but not their victims, has proved highly successful in curbing the yellow crazy ant population. Like the Borg, however, the interlopers do not give up easily, and the long battle continues, the standing death toll massive. For the time being at least, the red crabs continue to fill the streets for every November’s mass migration.

*****

It was the terror of the seas. Its name was spoken with fear and awe. It had weaved a path of destruction that was spoken of with disbelief in every port across the South China Sea. Now it’s luck was about to run out as it headed for the remote, palm-covered atolls known by their inhabitants as the Keeling Islands. The final battle was about to begin.

The infamous SMS Emden meets its match during the Battle of Cocos, one of the first naval conflicts of World War I.

Once the private retreat of a rich Englishman and his harem of forty Malay women, today’s Cocos (Keeling) Islands are a quiet adjunct of Western Australia and home to a small population of Europeans and Malaysians who make a living from tourism. Sitting about halfway between Australia and Sri Lanka, the Cocos have always been of strategic importance because of their location within major shipping lanes. This was all the more important in 1914 when the crew of the German cruiser SMS Emden, after months of successfully capturing and sinking almost every Allied ship it had encountered between Bengal and Keeling, decided to make for the Cocos and disable the vital wireless and cable relay on the archipelago’s Direction Island. Not only were the Cocos important to shipping during World War I, serving as a stopover point for ANZACS headed to the Turkish battlefield, but also a vital communications link between Australasia and Europe. For the other side therefore, it was an important link to sever.

The Battle of Cocos began on November 9th, 1914, when a landing party from the Emden stormed Direction Island and destroyed the relay station. Unbeknownst to the Emden was the fact that long before their plans of sabotage had been made, a convoy of ANZAC ships bound for Turkey were at this moment heading through the Indian Ocean. To make matters worse, one of the locals had managed to send an SOS to Allied forces before the communications station was damaged. Dispatched from the convoy to investigate the message, the Australian cruiser HMAS Sydney encountered and engaged the Emden in what would be one of the first naval battles of the war.

“It was the terror of the seas. Its name was spoken with fear and awe.”

The battle would prove to be fairly one-sided. While the Emden’s guns were capable of striking a target at longer range, the Sydney’s were more powerful, and after two hours of continuous fire, the wounded Emden beached itself on North Keeling Island. The Australian cruiser then pursued and disable Emden’s supporting collier, before returning to its original quarry four hours later. However, despite its battle damage, the Emden and its remaining crew refused to surrender, until two more direct hits from the Sydney convinced those aboard to hoist the white flag. The German casualties were high: 131 dead and 65 injured. All the survivors, including the Emden’s captain, the Hanoverian Karl von Muller, who had earned the respect of the Allies for his policy of treating captured crews with civility, were made prisoners of war.

Or not quite all: 50 of the Emden’s personnel, led by First Lieutenant Helmuth von Mucke, still remained on Direction Island. The original landing party, sent to wreck the communications relay, had never returned to their vessel and had witnessed its destruction from afar. Having annexed Direction Island and its population in the name of Germany, von Mucke realised he and his men would have to make a break for freedom before the Sydney came for them the next morning. He commandeered the nearby 123-ton schooner Ayesha, planning to head for the neutral territory of Dutch-controlled Indonesia. Strangely, the captured Cocossians were more than happy for the theft to take place, even willingly offering von Mucke and his men provisions for the journey. It was only when the curious First Lieutenant put to sea that he discovered the Ayesha’s truly dilapidated state. For von Mucke, the voyage back to Germany would be a long and arduous one, and an adventure that would ultimately make him an ardent pacifist and him at odds with Adolf Hitler in the future.

On Screen

Few film-makers have made use of the Cocos (Keeling) Islands outside of tourism. However in 2006, writer/director Jurgen Stumpfhaus and his crew visited the Australian territory to re-enact the Battle of Cocos for his two-part docudrama, Hunt The Kaiser’s Cruisers. Though made for German television, the miniseries was dubbed into English and screened in other parts of the world, as well as being given a DVD release. Episode 1, ‘The Caravan Of Sailors’, recreates the Emden’s dramatic rise and fall, as well as the fate of von Mucke and his men as they try desperately to get home through allied nations in the Middle East. Naturally, it paints the picture from the German side and even features an in-depth interview with von Mucke’s son, who understandably regards his late father as something of a hero. Von Mucke senior is portrayed as an unflappable leader of men, projecting an air of confidence he often did not feel for the benefit of his crew, and with an almost zealous belief in their survival. The kind of person you’d want to have on your side if you had to spend months walking through the deserts of Arabia and fending off warlords and bandits, for instance.

The Cocos really form just a small part of the program, but it stands as a rare example of their use in film and for that, Hunt The Kaiser’s Cruisers is worthy of mention – even if it is mainly enjoyable for the story that unfolds after the battle.

*****

Next Time

“War does not determine who is right – only who is left.” – Bertrand Russell

Somewhere in the fog-enshrouded Andean highlands of Columbia, a squad of soldiers is dispatched to a remote outpost to find out what happened to their missing comrades stationed there. However, attempts to unravel the mystery only beget more questions and before they know it, the soldiers are unwittingly re-enacting the fate of their predecessors. The claustrophobic thriller of The Squad next time on World On Film. See the trailer below.

Are You Sitting Comfortably? Part II

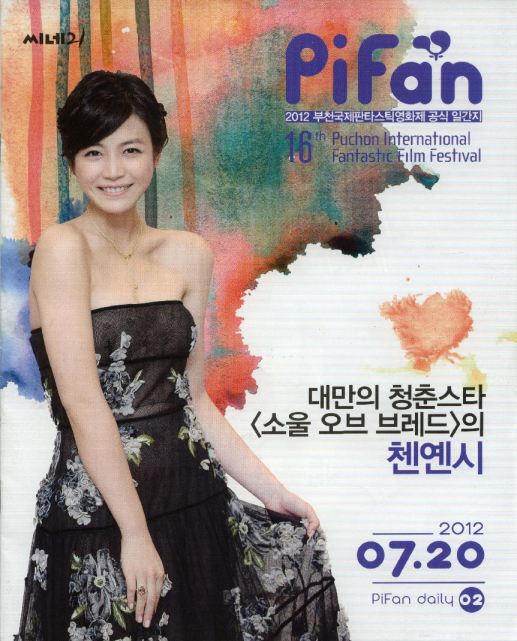

July 2012 saw the 16th edition of Pifan, or the Puchon International Film Festival, held annually in Bucheon, South Korea. I was there and you can read about the first half of my experiences in the previous post. Here, then, is the second half.

I’m sure it would surprise precisely no-one that a Korean international film festival is principally for Koreans. Even the Busan International Film Festival, the largest event of its kind in Asia, makes little more than a perfunctory effort to provide English to international visitors most of the time. I still haven’t forgotten the debacular mockery inflicted upon non-industry ticket purchasers at BIFF 2011, forced, thanks to the virtual impossibility it was to purchase online, to be herded like sheep along a rubber-ribboned maze toward a hastily-erected festival ticket booth outside the world’s largest department store only to be told the tickets had already been snapped up by everyone who’d arrived 30 minutes earlier. “Wow, thank you BIFF for selling 80% of the tickets online to everyone in the film industry and local government officials who probably won’t even turn up – not to mention relocating the festival to one single city block so this ocean of human slave puppets can fight like dogs for jacked-up hotel prices before standing in a queue on the street full of frustration and broken promises. This couldn’t be any more awesome even if I painted my nose red and let you pelt me with wet sponges – which, by the way, I completely deserve at this point.” Meanwhile, darting around the line of disillusioned faces like bright red sheepdogs, barked a zig-zagging group of festival volunteers wielding portable whiteboards onto which were scribbled a bizarre series of numbers possibly denoting how many dumb suckers were letting themselves be robbed of their dignity, but were in fact a rapidly-growing list of number codes for all the films selling out before you reached the booth. None of which was explained in English, and so became a time experiment wherein one determines how long it takes each mystified member of the cattle run for the penny to drop.

I’m sure it would surprise precisely no-one that a Korean international film festival is principally for Koreans. Even the Busan International Film Festival, the largest event of its kind in Asia, makes little more than a perfunctory effort to provide English to international visitors most of the time. I still haven’t forgotten the debacular mockery inflicted upon non-industry ticket purchasers at BIFF 2011, forced, thanks to the virtual impossibility it was to purchase online, to be herded like sheep along a rubber-ribboned maze toward a hastily-erected festival ticket booth outside the world’s largest department store only to be told the tickets had already been snapped up by everyone who’d arrived 30 minutes earlier. “Wow, thank you BIFF for selling 80% of the tickets online to everyone in the film industry and local government officials who probably won’t even turn up – not to mention relocating the festival to one single city block so this ocean of human slave puppets can fight like dogs for jacked-up hotel prices before standing in a queue on the street full of frustration and broken promises. This couldn’t be any more awesome even if I painted my nose red and let you pelt me with wet sponges – which, by the way, I completely deserve at this point.” Meanwhile, darting around the line of disillusioned faces like bright red sheepdogs, barked a zig-zagging group of festival volunteers wielding portable whiteboards onto which were scribbled a bizarre series of numbers possibly denoting how many dumb suckers were letting themselves be robbed of their dignity, but were in fact a rapidly-growing list of number codes for all the films selling out before you reached the booth. None of which was explained in English, and so became a time experiment wherein one determines how long it takes each mystified member of the cattle run for the penny to drop.

“This couldn’t be any more awesome even if I painted my nose red and let you pelt me with wet sponges – which, by the way, I completely deserve at this point.”

And again, this is the biggest film festival in Asia. It’s meant to be a big-name brand event designed to attract niche tourism. The more diminutive and less-funded Pifan, meanwhile, can be forgiven for lacking many of the needed resources, not least the ability to pave the streets next to the venues. Not only can the regular masses actually purchase tickets online, but also the staff is actually trying to make it possible for them to enjoy themselves. How else to explain BIFF’s red-shirted counterparts actually walking around with bilingual signage, or the fact that I was at one point assigned a personal interpreter so that I could enjoy a post-screening Q&A session?

Pifan is also trying to make a big name for itself, evidenced by the foreign film-makers and press I met there, and needs to be properly bilingual if only to draw that kind of crowd. I apparently cut an incongruous figure, being asked three times if I were “industry or press”, as though those were the only two options. Sure, there’s this blog, and I did act in a short film recently, but that wasn’t the point. I was there as an enthusiast. I can’t have been the only one. To me, international film festivals are an incredibly important service, offering average citizens a (relatively) rare chance to see something beyond the strong-armed monopoly of mainstream cinema. For half the price of a normal ticket.

Ironically, the mainstream played a much larger role in the rest of my Pifan experience, to mixed results.

The Shining

(1980) Written & Directed by Stanley Kubrick

“When something happens, it can leave a trace of itself behind. I think a lot of things happened right here in this particular hotel over the years. And not all of ’em was good.”

Yes, I know – surely Stephen King wrote The Shining? Not this version he didn’t. King’s celebrated novel tells the story of a recovering alcoholic with anger management issues trying desperately to do the right thing and hold on to his damaged family by accepting the winter caretaker’s job at remote Colorado mountain lodge, the Overlook, as a last-ditch chance to avoid poverty. However, his efforts to stay on the straight and narrow are completely disrupted by the hotel’s evil spirit, its power accentuated by his telepathic son. The story is a strong blend of the supernatural and King’s usual exploration of blue-collar family relationships put to the test by forces beyond their control.

Contrast this with The Shining, a story about a barely-under-control malcontent seemingly saddled with a family he doesn’t especially want taking a job at the Overlook in order to gain the peace and quiet he needs to write a novel. Quick to begin losing his sanity long before the hotel asserts its malign influence, this version of the character is the principle catalyst for the Amityville Horror-style rampage that follows, with the Overlook simply tapping into a pre-existing madness. While wrapped in similar packaging, the two stories could not be more different – and the above comparison barely scratches the surface of their asymmetry. Stephen King clearly agreed with this assessment, overseeing a televised adaptation of his book in 1997, which is, aside from the story’s climax, about as faithful as a four-hour miniseries can be.

“This is a man who could have made a film about the Yellow Pages and we’d all want to see it.”

And yet while The Shining both largely dismisses and tramples upon the source material, it has the kind of unsettling and claustrophobic atmosphere coupled with the trademark eye-catching cinematography and editing that make anything Stanley Kubrick does so compelling. This is a man who could have made a film about the Yellow Pages and we’d all want to see it. Add to this yet another force of nature in front of the lens in the form of Jack Nicholson, very much at the top of his game and with the kind of presence that superglues your eyes to the screen, almost afraid to see what he’ll do next. Jack Nicholson could perform the Yellow Pages and we’d all want to see it. Those of us still clinging to the remaining tatters of King’s original story have little choice but to declare him completely miscast as Jack Torrance – not because of One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest (I for one haven’t even seen it) – but because every nuance of his performance, every arched eyebrow, every glint in his eye and every cynical tone drawling from his lips telegraphs Torrance’s impending madness like flashing, ten-foot-high neon. Yet none of those people would actually say what he was doing on screen wasn’t interesting.

Then there’s that softly-disconcerting soundtrack by Wendy Carlos and Rachel Elkind intermingled with various classic found tracks of a different lifetime, the imposingly-dark brown visage of the Timberline Lodge-as-Overlook, the threatening majesty of Mt. Hood, and a whole raft of elements that make this psychological base-under-siege melodrama work so well. For King fans, it is an exercise in doublethink, where they must put aside the author’s middle American melodrama and enter Kubrick’s realm without any preconceptions. Imagine if King’s version of ‘The Shining’ was a true account of events, and The Shining is the fast-paced Hollywood thriller based on those events. Except that Kubrick was clearly seeing the story through an entirely different lens.

Room 237

(2012) Directed by Rodney Ascher

If you thought ‘The Shining’ ought to consist mostly of this opening shot over and over again, ‘Room 237’ is the documentary for you.

So imagine that you’re a fan of The Shining, and you’ve watched it over and over again in the 32 years since it was released. You know every line of dialogue, you’ve consciously studied every one of the set props, you’ve been struck by the symmetry of cross-fading shots, and you’ve stared at that opening shot of a helicopter flight across Lake St. Mary until the idea of it being just a helicopter flight across Lake St. Mary is patently absurd. Because you know Stanley Kubrick. Stanley Kubrick the perfectionist auteur who once made Shelley Duvall swing a baseball bat over and over again until she lost her mind. Stanley Kubrick the obsessive-compulsive director who turned a 17-week shoot into a 46-week shoot and had Jack Nicholson demolish 60 doors for the “Here’s Johnny!” scene. This is not a man who does anything by accident. Every one of those Spherical 35mm frames has been planned to the Nth degree.

All of which you know, of course. Now imagine someone decided to shoot a documentary where uber-fans like yourself get to discuss all the hidden meanings and themes you know are what Kubrick was aiming for.

This is Room 237, a brand-new celebration to deconstruction peopled by individuals who know The Shining better than you do and possibly Kubrick himself. Some of the theories aren’t new: there is long-debated good evidence to suggest The Shining is in part recreating the destruction of the Native Americans by the “weak” white interloper, likewise the Holocaust allegory has been around equally as long, and ‘everyone’ knows the film is one massive allegory for Kubrick’s tension-filled assignment to fake footage of the Moon Landing for NASA. The ‘Obvious When Pointed Out’ file is well-explored also, in particular Kubrick’s tendency to mess with a passive movie-going audience with visual non-sequiturs and provocative props just outside the first-time viewer’s field of vision. The suggestion that Kubrick’s face has been superimposed into the clouds in the opening sequence however, that a standing ladder is meant to mirror part of the hotel’s exterior architecture, or that if you play the film forwards and backwards simultaneously, you’ll see all kinds of intentional thematic symmetry, definitely belongs at the speculative end of the pool. However, the various attempts to reach beyond reasonable lengths at the film’s discourse are welcomingly absurd interludes between the more serious – and in all likelihood more accurate – interpretations of Kubrick’s work. Ascher neither wants nor expects us to take all of Room 237 seriously, and in so doing ensures his documentary doesn’t bear all the stomach-tightening hallmarks of an Alex Jones conspiracy piece.

Consequently, what you won’t find in this film are musings from cast and crew, or indeed what they thought The Shining was about. For that, Vivian Kubrick’s 35-minute on-set short is still the best bet. Room 237 is a light academic paean to the film which spawned it, and for fans, is definitely worth a look. Everyone else will probably wonder what the fuss is all about.

3-2-1…Frankie Go Boom

(2012) Written & Directed by Jordan Roberts

The Pifan Daily, freely available during the festival. Apparently I missed the meeting where the word ‘daily’ was redefined to mean ‘twice-only’.

Time now to unzip our parachutes and float down to Dick Joke Island, where relative newcomer to film Jordan Roberts, perhaps in a bid to prove our species really did evolve from primates, clearly believed the market needed another 90 minutes of genital-related humour, now that Harold & Kumar have annoyingly grown up. The infantile Frankie Go Boom also inflicts upon the viewer that other ‘essential’ element of frat-boy comedy, the intensely annoying main character one is supposed to find loveable and hilarious. Twenty years ago, it was the disturbing mental case brought to life by Bill Murray in What About Bob?; today, it’s Chris O’Dowd donning an American accent to play the sociopathic Bruce, a young man oblivious to the lifelong psychological trauma he has inflicted upon his younger brother Frankie by filming every one of his most compromising moments and screening them to a giggling public – a practice all the more destructive in the age of file-swapping and broadband. Add the obligatory ‘touching’ romance, ‘crazy’ and unsympathetic family and Ron Perlman sacrificing the last vestige of his dignity, and presto: another tedious trek through the teen mire. You know, maybe we could get Scorsese interested in that Yellow Pages idea.

Puchon Choice Short 1

Another collection of short films, of which the quality averaged slightly lower than last time. Things get off to an uneven start with the Korean black comedy, The Bad Earth, where office employee Seung Bum puts himself at odds with his co-workers by refusing to clap along during company presentations and after-hours reverie. Clapping, as Seung Bum, firmly believes, is in fact an insidious form of alien virus that makes the human race ripe for the plucking. I will credit film-maker Yoo Seung Jo for adding to the shallow waters of sci-fi in Korea, a genre the country has historically had little reason to explore. However, the story’s premise is a little too ludicrous to be taken seriously, even if Seung Bum just might have good reason for believing it.

Very little credit, meanwhile, should be afforded Han Ji Hye, who in The Birth Of A Hero quite shamelessly takes the ‘Rabbit of Caerbannog’ scene from Monty Python & The Holy Grail and transposes it onto a rooftop in downtown Seoul. The idea that he might possibly be ignorant of this hallowed source material evaporated once the otherwise docile white rabbit began flying through air towards its victims and gouging out their necks in precisely the same manner. If Han is lauded as a master of surrealist cinema after this unbelievable cribbing, he deserves to be fed to the Legendary Black Beast of Aaaaarrrrrrggghhh!

Quality began to reassert itself at this point to the unusual Korean stop-motion animated short, Giant Room, in which a man rents out a space in a strange, colourless building. Told explicitly by the landlord not to enter the room marked “Do not enter this door”, the newcomer ignores the warning to his great peril. It’s always hard not to be impressed by the work put into old-style animation – just getting 10 minutes of useable material must have taken months. The claustrophobic miniature sets are also well-designed, and the decision to abstain from dialogue a good complement. Hopefully this is not the only feature we will see from Kim Si Jin.

“I will credit film-maker Yoo Seung Jo for adding to the shallow waters of sci-fi in Korea, a genre the country has historically had little reason to explore.”

The drama finally moved overseas at this point for the dystopian US horror, Meat Me In Pleasantville. It is the near future, where overpopulation has finally used up all of the world’s meat reserves, causing the federal government to make cannibalism legal. Inevitably, some citizens agree with this decision more than others, particularly dependent upon who is at the other end of a meat cleaver at any given time. As the Pleasantville population’s taste for human flesh turns them all into murderous zombies, a father and his daughter fight to escape, though they too are only human. Fans of slasher horror will not be swayed too much by the gore of Greg Hanson and Casey Regan’s half-hour kill-fest, though the real-world basis for the story would, I think, amuse George Romero. It’s a little difficult to imagine a government making cannibalism legal, or that a population would ever go through with it, but anyone who thinks that humans couldn’t acquire a taste for their own flesh – or want to keep eating it after that first bite – ought to read the real-world story of one Alexander Pearce. Unfortunately, both acting and dialogue fail to match the worthiness of the concept, making Meat Me In Pleasantville a little hard to digest.

The theme of vampirism returns in fellow US horror short, The Local’s Bite, where a young woman traveling home via ski lift after a night out with friends tries to evade a stalker. Film-maker Scott Upshur puts the unusual transport system common to his local town to good use in this suspenseful drama, which squanders its build-up at the last moment for unrealistic fantasy in the name of plot twists and humour. And again, the acting is highly variable, with the horribly wooden appearance of a clearly real-world ski lift operator struggling like mad to deliver a single line. However, Upshur’s talent for rising tension, good location choices and decent editing cannot be ignored, and those are the areas he should focus upon in the future.

It was the final entry in the collection, Antoine & The Heroes, that proved most enjoyable. In the French comedy-pastiche, B-grade film obsessive Antoine is forced to choose between two simultaneously-screening films at his local cinema complex, each showing his two favourite screen stars and each on their final showing. Unable to decide, Antoine decides to watch both, dashing back and forth between cinemas to catch the highlights. Hailing from the days when kung-fu couldn’t be achieved without a funky disco track and heroines screamed and screamed without ever needing Vicks Vapodrops, cool cat Jim Kelly beats up the baddies without messing up his bouffant in his latest piece of kung-fu cinema, while long blonde silver screen star Angela Steele dodges groping zombies in her new horror blockbuster. At first, Antoine manages to alternate between the two spectaculars with ease, but a small accident results in the blending of realities, films and genres to comedic effect. The best thing about this film is Patrick Bagot’s excellent pastiche of 70’s style kung-fu and B-grade horror – both very much in-vogue during that hirsute decade – realized by some great acting, costumes, sets, and appropriate period soundtracks. Anyone with childhood memories of 70s pop culture will feel more than a little nostalgic by the end of Antoine & The Heroes, reminded of why it was all so much fun – even if it does look ridiculous four decades on.

*****

Next Time

“From all directions They come, caring nothing for demarcation lines between man and motor. On every pavement, in every street, across every veranda, and through every backyard, they cover the town in a scuttling sea of red.”

World On Film pays a visit to Christmas Island and comes face to face with its most colourful inhabitants – a sidestep from the usual film fare, next time.

Are You Sitting Comfortably? Part I

In this edition of World On Film, I look back over my visit to the recent Puchon International Fantastic Film Festival (Pifan), and give quick takes on the screenings I managed to catch.

In this edition of World On Film, I look back over my visit to the recent Puchon International Fantastic Film Festival (Pifan), and give quick takes on the screenings I managed to catch.

I’d been wanting to catch Pifan for a few years now, but always somehow managed to forget when it was on. However, after the complete debacle that was BIFF 2011, it was time to get serious about it. For those wondering, Pifan takes place in Bucheon, a city in the Korean province of Gyeonggi, located roughly halfway between Seoul and Incheon. There are eight categories, including World Fantastic Cinema, Ani-Fanta, and Fantastic Short Films. Only one category, Puchon Choice, is competitive, with the winners being screened on the final weekend of the festival. This is Pifan’s 16th year, making it almost as long as its counterpart in Busan.

Physically-speaking, Pifan is smaller than BIFF, and organised much the way BIFF used to be, ie – with screenings sanely distributed across in a number of cinemas throughout downtown Bucheon with one particular venue, Puchon Square, at the centre. It has yet to become the almost industry-only event that is BIFF today, which in practical terms means the average joe can actually get tickets for this thing both online or by simply turning up to the ticket offices in timely fashion. There’s no insane queuing for hours, no giant department store you have to trek through with huskies just to reach a screening, nor the feeling that if you aren’t press or industry, you’re getting in everyone’s way.

On the flipside of this, Bucheon is hardly the most exciting city to hold a festival, the main street seems to be in a permanent state of construction, and the more modest department stores in which the cinemas are located don’t have the greatest selection of cuisine. On balance however, I had a very positive experience, so I aim to make the best of Pifan until it inevitably becomes so successful that getting tickets for screenings will become as difficult as convincing Adam Sandler to stop making movies.

I managed to catch something from most of the categories mentioned during my visit. Here is what I saw:

Hard Labor

(Brazil, 2011) Written & Directed by Marco Dutra and Juliana Rojas

Sao Paolo housewife Helena is about to realise her dream of starting her own business in the form of a neighborhood supermarket. Yet just as she is about to sign the papers for the property lease, her husband, Otavio, is fired from his job as an insurance executive after ten years’ faithful service. However, the couple decides to risk the investment and the store opens, though for some reason, business just doesn’t seem to be taking off, seemingly in direct proportion with Otavio’s failure to find work and mounting alienation from the family. As an increasingly-stressed Helena struggles to hold everything together, she finds her attention drawn to a crumbling supermarket wall and wonders whether it might hold the answers to her problems.

“There’s no insane queuing for hours, no giant department store you have to trek through with huskies just to reach a screening, nor the feeling that if you aren’t press or industry, you’re getting in everyone’s way.”

For much of its screen time, Hard Labor is more a drama about family breakdown than it is a horror movie, which is especially important for horror fans to bear in mind when going into it. Although there are definitely supernatural elements to the story, they are there to be allegorical, to act as a catalyst for the primarily human conflict which takes place. The problem for me at least is that neither of these elements quite reach the crescendo they could have had and there is a little too much stillness throughout. It isn’t really until the final scene that I felt the two strands really came together, but that does mean that Hard Labor has a satisfying ending. Anyone who’s ever had to face long-term unemployment through no fault of their own will appreciate the film’s central message that to get by in this ultra-competitive world, you sometimes have to unleash the inner animal. Good casting choices, lighting, and set construction also help to push Hard Labor over the line, along with the occasional dash of dark humour.

The Heineken Kidnapping

(Netherlands, 2011) Directed by Maarten Treurniet Written by Kees van Beijnum & Maarten Treurniet

Rutger Hauer stars in Maarten Treurniet’s interpretation of ‘The Heineken Kidnapping’ (image: Pifan Daily)

As its title suggests, The Heineken Kidnapping retells the true-life incident when in 1982, Alfred Heineken, then-president of the family business, was kidnapped by four individuals for the ransom money. Based loosely on the events as reported by Peter R. de Vries, the film focuses on the careful planning, abduction, and aftermath of the event, in which the traumatised Heineken struggles to cope with his imprisonment as well as fight various legal loopholes in order to bring the criminals to justice.

Since its release, the film has been criticised for playing fast and loose with the facts of the case, as well as glossing over the highly meticulous planning the four young men undertook before making their move. I therefore probably had the advantage of ignorance, in that I had never heard of the kidnapping before, and simply took what I saw at face value. To me, The Heineken Kidnapping was a fairly compelling crime drama with a strong cast, most notably in the form of Reinout Scholten van Aschat as the psychopathic young Rem Humbrechts, for whom the operation is as much for sadistic pleasure as it is for financial gain. Meanwhile Rutger Hauer turns in a strong and sympathetic performance as Alfred Heineken himself, which, given that the audience is being asked to care about the plight of an extremely wealthy adulterer, is a testament to the actor’s longstanding talent. Those more familiar with the source material may feel differently, but for me at least, The Heineken Kidnapping was an enjoyable example of Dutch cinema, and proved to be one of the more talked-about entries at Pifan – at least going by some of the people I met during my visit.

Extraterrestrial

(Spain, 2011) Written & Directed by Nacho Vigolondo

When a series of flying saucers begin hovering over the cities of Spain, most of the population takes to the hills. However, for Julio, a young advertising artist in Cantabria, the more pressing concern is to stay as close to Julia, the girl of his dreams, in whose apartment he has just spent a passionate evening. Unfortunately, matters are complicated by the presence of Julia’s nosy next-door neighbour and the return of her longtime boyfriend. But Julio will do anything to be with the girl he loves – even if that means making up a convoluted series of lies about an alien invasion – just to stay on the premises.

“At its core, Extraterrestrial is really a pretty conventional romance-comedy that hits all the usual notes its well-worn formula demands.”

With dramatic shots of a saucer hovering above urban skyscrapers and dire warnings by the authorities to stay out of harm’s way, one could be forgiven for thinking that Extraterrestrial might be another District 9. However, as with Hard Labor, the fantastical elements of the script serve merely to push a group of individuals together into a confined space and add colour to the background. At its core, Extraterrestrial is really a pretty conventional romance-comedy that hits all the usual notes its well-worn formula demands, and the unusual setting little more than an elaborate misdirection. That said, it is a pleasing enough 90 minutes with some enjoyable humour, and Julian Villagran makes for an unconventional romantic lead. Nonetheless, would-be viewers are advised to set their phasers on ‘low expectations’ for the best result.

Spellbound (aka Chilling Romance)

(South Korea, 2011) Written & Directed by Hwang In-ho

Yuri, a shy young woman living in Seoul, is haunted by the ghost of her dead schoolfriend who lost her life during an ill-fated class excursion. Desperate for human company, Yuri has resigned herself to the fact that she will never enjoy close friendships or romance as long as a malignant ghost frightens away anyone who comes near. Hope comes in the form of Jogu, a wealthy stage magician who becomes intrigued by Yuri after he hires her for his illusionist act. With everyone else running from her in fear, will Jogu’s affection for his star performer be strong enough to overcome resistance from the Other Side?

I’d been warned before the screening began that Spellbound was something of a corn-fest, and by the end credits, felt so overdosed on saccharine, I nearly checked myself into a medical clinic for a diabetes test. In a country where clichéd melodrama is so popular it’s a major international export, Spellbound does not stand out from the crowd. With every passing minute came cliché after tired cliché about ill-fated romance, and every stomach-churning line about love and dreams meticulously welded to a truly nauseatingly-twee soundtrack had me twisting in my seat and groaning like an old man putting Viagra to use for the first time. If Extraterrestrial was formulaic, Spellbound was the formula, right down to the wise-cracking but experienced friends and sidekicks of the lead characters. All of which was so overwhelming that the horror element to the story, and raison d’etre for the whole situation was never adequately built up to be anything especially convincing and had me longing for the Dementors to float in on special dispensation from Azkaban and suck everyone’s souls into oblivion. Son Yeji gave a creditably agonised performance as the long-persecuted female lead, but frankly, the entire cast could have simply sat in a pool filled with corn syrup and elicited the same drippy performance. That, at least, would have been more honest.

Fantastic Short Films 7

Postcard for the Korean short film ‘The Metamorphosis’, handed out to patrons as they entered the cinema for the ‘Fantastic Short Films 7’ collection.

The great thing about short film collections is that if one film proves awful, you don’t have to wait long for the next one. FSF7 however started strong, with the Korean entry Delayed, in which a young middle-aged woman waits patiently at a near-deserted train station for her husband to arrive. Yet as she strikes up a conversation with an inquisitive man claiming also be expecting an arrival, nothing seems to be quite as it appears. Cast and crew of this very moving short appeared live on stage at the end, where director Kim Dong-han explained his desire to connect lost souls with lost train stations. My thanks to the Pifan personal interpreter who sat with me during this unexpected bonus event!

Next up, the Japanese parody-pastiche Encounters, wherein two very good friends look for adventure in the countryside and find more than they bargain for with giant monsters roaming the streets thanks to the machinations of an evil professor. Shot entirely using plastic action figures and some deliberately wonky props and sets, Encounters is a tongue-in-cheek Godzilla-like comedy, complete with lame action sequences and bad dialogue. I’d like to think the English subtitles weren’t meant to be quite as poor as they were, but if so, mission accomplished!

“The quality then takes a serious nosedive with the unpleasant and forgettable Italian horror mish-mash, I’m Dead, and I certainly wished I’d been dead during the 17 minutes it screened.”

The quality then takes a serious nosedive with the unpleasant and forgettable Italian horror mish-mash, I’m Dead, and I certainly wished I’d been dead during the 17 minutes it screened. Two long-time friends out hiking in the forest suddenly find themselves kidnapped by a crazed religious fanatic who begins torturing them in his secret underground lair, replete with bad lighting, corpses and handy tunnel system. The pointless and gruesome tale offers no depth in terms of the reasons behind the mad psychopath, nor indeed the ridiculous twist at the end. Which is an interesting coincidence, because I can offer no reason why anyone should watch it.

The macabre continues – though in a very different style – in the form of the Korean silent film, The Metamorphosis, a shadowy sepia affair with the disconcerting performances of Eraserhead and the visual echoes of Nosferatu. Claustrophobic static shots combine with heavy industrial clanking and retro white-on-black dialogue text inserts to tell the story of a family beset by vampirism. In truth, it’s a great example of style over substance that adds little storywise to the genre and comes close at one point to mobs with burning torches. Yet it’s the style that proves the most compelling here, so that while I’m not entirely sure what I saw, it was impossible to take my eyes off the screen. There are plenty of music videos like that.

Rounding out the collection was the light-hearted martial arts/crime spectacular, Pandora, in which taekwondo trainee Jeong Hun arrives in the city of Chungju for a performance, only to accidentally switch his cell phone with that of a man on the run from a gang intent on seizing the secrets the identical device contains. The film is a fairly unremarkable, reasonably-paced runaround that could not possibly satisfy fans of martial arts films, offering nothing new by way of story or visuals. When a story is full of clichés that have been done better elsewhere, you have to wonder who the intended audience really is. As a 30-minute romp in a film festival, Pandora is sufficient eye candy, but on its own, it swims in crowded waters.

*****

Next Time

The second half of my Pifan retrospective. I finally get to see Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining on the big screen, watch the over-reaching new documentary about the very same, entitled Room 237, find myself underwhelmed by the new Harold & Kumar-style American feature, 3-2-1…Frankie Go Boom and sit through another short film collection with mixed results. That’s World On Film next time.

Keys Of The Kingdom

It’s time to visit the Middle Kingdom, where, deep in the Chinese countryside, we find state ideologies reinforced and a generation’s final journey as World On Film explores

Postmen In The Mountains

(1999) Directed by Jianqi Ho Written by Wu Si

“A boy is a grown up when he carries his father on his back.”

‘Postmen In The Mountains’ is a passing of the torch film, where change is not a virtue of the society in which it takes place.

“Choose a job you love”, said Confucius, “and you’ll never have to work a day in your life.” Good advice, though for some, a more realistic saying might be ‘Keep choosing jobs until you find one you don’t want to give up.’ Learning after all comes through experience, and love through understanding based on experience. Confucius also advocated that one should unfailingly obey their parents, which in practice has often meant the parents choosing one’s job for them. A good son or daughter in turn accepts that their parents chose wisely and loves them for taking such an active interest. Thus they are expected to come to love, rather than choose from an internal desire, the work they will do with their life. Or at least that’s the practical application of Confucian thought, which has been deeply embedded in the Chinese psyche for centuries. Postmen In The Mountains is very much a demonstration of this thought, and in so doing advocates a strict code of obeisance to authority that puts the viewer in little doubt as to why a government that strongly controls the local entertainment industry would give its production the green light.

This does not mean, however, that Postmen In The Mountains is neither enjoyable nor impenetrable to a non-Asian audience. Putting aside its uncomplicated surrender to prevailing doctrine, the film is essentially a ‘passing-of-the-torch’ adventure between a father and his son, as one takes over the other’s physically-demanding job of delivering the mail on foot to remote villagers along a 115km circuit through the mountains of China’s Hunan Province in the early 1980s. It is a job that requires extended periods away home and thus father and son have until now been strangers to each other, truly developing their relationship for the first time because of the father’s decision to accompany his successor for his first trip in order to show him the ropes. The son in turn is eager to demonstrate his capabilities, but finds that being a postman is not as easy as it looks.

Rural China’s various minority cultures add color to the postman’s delivery route, such as the Tong peoples of Hunan province.

It was by contemplating a Westernised version of this same basic story that I found myself highlighting the uniquely Chinese character of the film, which, for the purposes of this blog, made it an all-the-more-suitable entry. Since Occidental child-rearing involves the fostering of independence within the young so they will be able to achieve adulthood, a Western version of the story would have the two lead characters at great odds with each other. There would be the inevitable falling out scene where one character would truly hit a nerve, until the equally-inevitable resolution and understanding by the closing credits. The whole affair would swerve dangerously close to melodrama and be hailed as a great emotional rollercoaster ride.

All of which would be completely unthinkable in the Chinese mindset, where elders are to be unfailingly obeyed and a shouting match might lead to disownment. We are of course speaking generally here, but so is the film. Thus it is in Postmen that the conflict between the generations is much more of an undercurrent, and even when it does surface, is comparatively little more than mild disagreement. We therefore learn of internal fears and resentments primarily through a series of flashbacks to both characters’ earlier days in order to develop our understanding of not only the reasons for their behaviour towards each other in the here and now, but also as to why their shared three-day journey is so monumentally-important for them.

“Postmen In The Mountains advocates a strict code of obeisance to authority that puts the viewer in little doubt as to why a government that strongly controls the local entertainment industry would give its production the green light.”

In turn, where the Western version would emphasise the negative aspects of the conflict in order to telegraph emotional angst, its extant Chinese counterpart focuses more on its positive aspects – in other words, how understanding and harmony is achieved through father and son as a result of their time together.

Being part of the community is as much a part of the job as delivering letters, especially for those living in isolation.